Quantum physics is a relatively new scientific field, and somewhat used and abused by writers in its brief lifetime. Benjamin Labatut has made a career out of forging a cheap equivalency between quantum uncertainty and modernist malaise, and the whole postwar generation of postmodernists used it as a crutch – sometimes well, sometimes clumsily – in order to bring a sort of swerving indeterminacy to their work. (Thomas Pynchon admitted he had bungled the concept of “Entropy” in that same-titled story – though it’s still a good story, I think, especially for an early work – but redeemed himself with Gravity’s Rainbow and all his other quantum-flecked novels after that. He didn’t call himself a slow learner for nothin’!) The best quantum-inspired novels hung uneasily over a howling void of chaos, accepting a radical narrative possibility; the worst ones used it to get out of a plot corner. Well, according to science, anything could happen… and so it did, right when I needed it to! (We can separate this from magic realism, which never asks for explanation.) That’s an idiot’s understanding of quantum physics (and, incidentally, of religious faith – see Smeryedakov in Brothers Karamazov asking if God would move a mountain right when He was asked) and, in our Idiot’s World, the one that most persists – quantum physics as the get-out-of-certainty-free-card. My own idiot’s conception of quantum physics imagines it more as science reaching the end of knowledge, of being able to even name the phenomena it is observing (or not observing); coming up, like Wittgenstein, to that of which we cannot speak. We know that there’s something we don’t know, and most likely can never know.

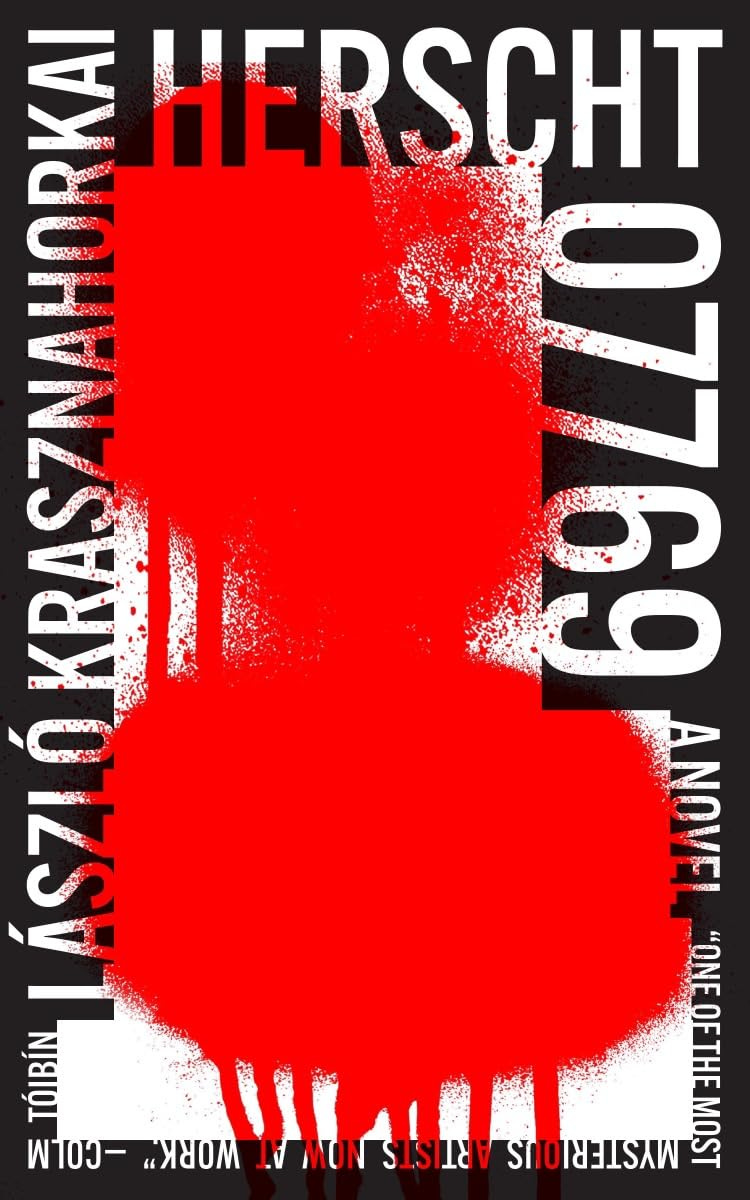

An idiot’s understanding of quantum physics is all you need for Laszlo Krasznahorkai’s latest novel, Herscht 07769 (translated by Ottilie Mulzet, and out now from New Directions), as it’s the central animating fear of the book. Our idiot - or our Idiot, in the Dostoevsky-ian sense – is the good natured giant Florian Herscht, one of Krasznahorkai’s classic village simpletons, a gigantic man with a small child’s innocent view of the world; Florian has taken some night classes at the local university and become consumed by the fear that, because of the great cosmic uncertainty that underlies the natural world, society is at the risk of imminent collapse into a vacuum of pure emptiness. His professor, Herr Köhler, tries to reassure Florian that he’s not quite correctly understanding the science, but Florian continues to spiral, going so far as to write impassioned letters to Angela Merkel, warning her of the coming catastrophe:

… the essence, he would explain – if uninterrupted by Mrs. Merkel – was that inasmuch as that one surplus material particle inexplicably emerged during the Big Bang, we cannot exclude the possibility of the emergence – just as inexplicable, caused by the same breaking of symmetry, after one billion antiparticles and one billion particles – of one surplus antiparticle; it could occur, just as incomprehensibly, resulting in the birth of a reality composed of antimatter, and what this means for us is (Florian had decided to say this much and nothing more the previous night when he’d had enough of tossing and turning and left for the rain tracks one hour early) – what this means for us here is catastrophe, not merely on this Earth, not merely in our own galaxy, but in the entire universe, because if the universe of matter collides with the universe of antimatter, then – in Florian’s estimation – both would be immediately annihilated, meaning that Something would disappear, and that which bears the opposing sign would not remain, or, as Herr Köhler might phrase it, the Anti-Something with its opposite charge would not remain, meaning the supervention of Nothing for us: everything in the universe would return to where we started out, to that Deathly Light which, for us, is identical with Nothing, in vain is the existence of this Nothing disputed, the very first geniuses of civilization trembled from the mere thought of this Nothing, but we do not have to tremble, we must face facts, face the Great Dialogue between Something and Nothing, something must be done…

When he’s not writing his letters, he works for a graffiti removal company, and otherwise completes odd jobs around the small east German town of Kana, lending his immense strength out in exchange for a free meal or two, a running tab across town. The graffiti removal company just happens to be run by a Neo-Nazi, “the Boss,” who’s obsessed with upholding the cultural heritage of Germany, specifically the glory of Bach. The Boss is just waiting for the right time to fully induct Florian into his Neo-Nazi cell, taking advantage of his brute mass, but Florian’s natural naïveté and simple goodness prevent him from ever actually joining the fray:

… Florian knew he had no desire to be part of them, he was afraid of them, all of Kana knew about them: Nazis, people repeated in lowered tones, which made the Boss’s ever more belligerently expressed wish even more threatening, because if Florian signed up with the unit, then he would have to struggle, day by day, not only alongisde the Boss (with full devotion), but among these Nazis too (of course with no devotion), as he could be certain – he knew them well enough – that they wouldn’t leave him alone, he’d be under pressure to get tattooed, and he was more afraid of this tattoo than the dental clinic, he had no wish to be tattooed, no Iron Cross, no red-tongued German federal eagle which the Boss had been recommending vehemently, Florian got goosebumps on his arm just thinking about the needle and the tattoo machine with its frightening whirring sound which he himself had heard on occasion when accompanying the Boss, after rehearsals, to Archie’s studio as another newer or older member lay down beneath the machine while the others waited outside, he felt like running away, insensate, in the opposite direction from where this needle and this tattoo machine were operating – no, no to his, and inasmuch as he felt able, he even pronounced it decisively aloud, no, he was never going to have himself tattooed, that wasn’t his style, he added softly, at which, of course, the Boss’s face turned crimson in rage: what, you don’t belong with us?! you do belong with us!! …

Krasznahorkai is no stranger to long sentences and blocks of uninterrupted text, but Herscht 07769 takes this trend to its logical extreme: the whole book is composed of one sentence stretched across four hundred some pages. Like those films that claim to be one take but actually have a bunch of hidden cuts in them – Birdman, to give a less-than-stellar example – or some other ‘one sentence’ novels – Jon Fosse’s Septology, Lucy Ellmann’s Ducks, Newburyport – there are actually plenty of internal punctuation marks within the text, dialogues tagged with question marks, exclamation points galore, adventurous em-dashes, comma-spliced reloading repetitions that keep the rhythm rumbling along, and a number of of load-bearing semi-colons where your average editor would place a nice break. However, there is a restless energy within this Bernhard-ian attempt at one unbroken thought, and where other novels might involve quantum physics within the plot of the novel, Krasznahorkai goes one step further, making the structure of the novel itself swing wildly between matter and anti-matter, between order and chaos. There are beautiful, florid sections on music and the harmonics of Bach, and only a couple pages later, and of course within the ‘same’ sentence, there are expletive-filled xenophobic rants leading into actual car crashes, or simple acts of violence, and then another couple pages will go by and you’re in a scene of bucolic village friendliness, a reflection on the nature of true camaraderie between longtime companions. Herscht 07769 is always propulsive but also always veering from side to side, traveling the maximum possible distance to cover a straight line. At times these veers are compressed within a couple lines, as in the Boss’s simultaneously sacred and profane speeches on the majesty of Bach:

… it’s all in my little finger, and listen, because when we start playing whatever it may be, the umpteenth opus of this or that in D major, then I’m in the universe, get it?! because this is the universe, fuckit, because you were born, or at least you were dropped on your head, here, in this exceptional place, where we are not born as halfwits, and I’m going to beat that imbecility out of your head and I’m going to beat Bach into it…

Plot is almost tertiary behind Krasznahorkai’s structural and stylistic choices, but he does fill Herscht 07769 with plenty of it. The Boss’s group becomes more and more militant, especially as the Bach Museum is targeted by graffiti taggers, leading to a series of random bombings and conflagrations around the area, some of them false flags attacks, a Krasznahorkai specialty; Florian becomes so obsessed with warning Merkel about quantum catastrophe that he goes directly to the Bundestag and becomes something of a person of interest; Herr Köhler mysteriously vanishes without a trace, either taken by the authorities for his expertise or somewhere more mysterious; and wild wolves begin appearing in the area, coming down from the mountains and attacking humans. Underlying these big bangs is Krasznahorkai’s typical focus on quotidian small town life: the local orchestra is trying to learn Bach; the local pubs and hotels struggle with a lack of tourist income; the local honey hawker struggles to find repeat customers; a lonely and talkative widow wants to start a local poinsettia competition, but can’t understand why nobody will open their door to a neighbor during a bombing streak; and oh yeah, it’s sometime in the late 2010s, early 2020s, and some kind of virus is spreading worldwide? These swings between action and repose are another layer to Krasznahorkai’s quantum schema, both states existing simultaneously, the negative memory of one hanging uneasily over the other even as things move along. As in all of Krasznahorkai’s novels, his eye is equally trained on the squalid and the beautiful, the low and the transcendent, the abyss and the higher heavenly world; one can’t be seen without the other. As an increasingly feral and Bach obsessed Florian reflects:

… Bach was a STABLE STRUCTURE and would remain so for all eternity, something like an ideal, like a fairy-tale crystal, like the surface of a drop of water, its stability indecipherable, its perfection indecipherable, and of course this could be described, but it could not be grasped, because its essence sidestepped the movements of the spirit that attempted to grasp it, because there are things of which we are not capable, thought Florian’s brain, and that is natural, and yet for us to understand why there is no essence of the perfect, that is why we must say that the perfect merely exists, but if it lacks essence, then only wonder remains to us, this is what Florian’s brain was thinking…

When you write one long sentence, attention naturally falls on that last period; regular novels have the advantage of taking a couple breaths beforehand, whereas the momentum of one sentence cascading towards the end makes a reader wonder: well? how’s he gonna pull this off? Krasznahorkai continues to up the gambit till well near the end, introducing more and more escalations as the pages dwindle; Florian (thankfully) turns against the Nazis and makes his own transition from order to disorder, becoming a creature of nature rather than a misfit in society, while nature itself is twisted, by human intervention, into something unrecognizable, and both are brought together in the end in a sublime final image that I could not even spoil even if I tried, besides saying: goddamnit, Laszlo, you really did pull it off. For nearly every other writer, a one sentence novel structured around and about quantum physics, focusing on a Myshkin-esque giant with superhuman strength, that also touches on Europe’s resurgent right wing and the breakdown of social trust, would be one gimmick too many. But Krasznahorkai, like the geniuses he reveres – Kafka, Dostoevsky – is such a virtuoso as to make anything work. I’m no quantum scientist, but I’m fairly sure anything really can happen, even a masterpiece emerging out of the horrifying void of the present.

You can get Herscht 07769 at your local bookstore, local library, or online at Bookshop.org, where purchases support independent bookstores around the country. (Buying from that link will also contribute in a small way towards this newsletter.)

If you liked this post, please share it with a friend!

Previous writing on Krasznahorkai: