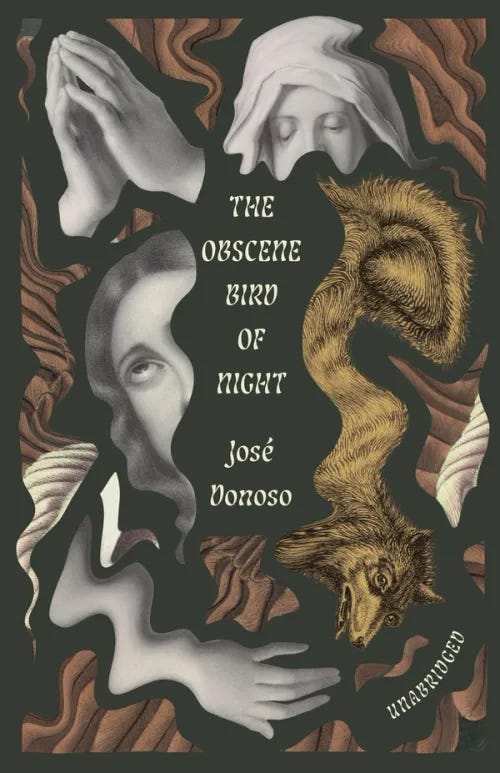

There are certain books that require a bit of maneuvering when you’re reading them on the subway, lest someone get the wrong idea from the title. Christina Stead’s The Man Who Loved Children was a particular challenge, its many pages requiring many subway trips angled downwards so no one thought I was reading some pedophile book; Roberto Bolaño’s Nazi Literature in the Americas presented similar issues, especially after a fresh haircut. There are other books which present more benignly but must be hastily tucked away in bags before entering conversation with family, coworkers, or acquaintances, lest they innocently ask about what you’re reading. Oh, this Bernhard novel Correction? It’s a really elegant argument for suicide, it’s great! Oh, Bolaño’s 2666? This little thing? Just about these women getting raped and murdered in the desert of Mexico, yeah, I’m really… enjoying it? Anyway, how’s the family? Jose Donoso’s The Obscene Bird of Night, the Chilean author’s 1970 novel recently reissued by New Directions with 20 pages of previously untranslated added to it (thanks to translator Megan McDowell, aiding original translators Hardie St. Martin and Leonard Mades), immediately rockets up to the top of the ‘not for polite company’ list. The Obscene Bird of Night is undoubtedly a masterwork, but it’s also a parade of abject horrors, a grimy labyrinth that leads mostly to disgust, a paranoid body horror freakout. Thankfully, I only read this one around my wife and my dad, who would periodically check in about what was happening in my ‘freak book,’ and I could regale them with the latest nasty corner that Donoso had led me into. In less than polite company, reading and sharing the book can be a bit like the Curb Your Enthusiasm episode where Larry David and John McEnroe are enthralled by the “Mondo Freaks” book:

Oh God!!! Three legs!!! What is that!?!?!?! The Obscene Bird of Night features, non-exhaustively, all this and more: witches with sexual powers and braying dog familiars; withered old crones fighting over scraps of junk; a mythical flying head-beast called the chonchon; a papier-mache Giant’s head rented out by a pimp for sex with an orphaned prostitute; a group of ‘monsters’ paid by a rich landowner to create an inverted Garden of Eden populated exclusively by ‘freaks’; a kind of human ship of Theseus scenario where someone’s organs and blood are slowly and methodically transplanted for various monster parts, “… with their phosphorescent snouts, the animals are tearing me to pieces, they’re destroying me with their fangs, their steaming tongues, their eyes that drill holes into the night, as the snarling beasts rip me apart, snatching up hot chunks of my viscera so that Dr. Azula can take them for himself, splashing about in the pool of my blood, fighting over my guts, and cartilege, ears and glands, hair, nails, kneecaps – each organ of mine that’s not longer mine because I’m no longer me but these bloody scraps of flesh”; old women acting as babies for young possibly pregnant women, including feeding and changing; and, most crucially, the imbunche. What’s an imbunche, you might be asking, if you haven’t already quickly closed this email because your boss might be looking over your shoulder at any second? I’m glad you asked! The imbunche is a piece of Chilean folklore wherein a child is kidnapped by witches and turned into a fetish by means of tying one of its legs to its neck and sewing up all of its orifices. Said imbunche is then placed at the entrance to a witches’ cave, serving as a kind of dark magic guard / personal assistant that shuffles around on three limbs and can only communicate with guttural noises.

Now, I’m sure most of you have already rushed out to buy this book just based off that list of sordid particulars, but in case you need further selling, The Obscene Bird of Night is a brilliant, long-overlooked work, one that not only challenges ideas of what the novel can be, but will also make you rethink what a human can be. It is a book of many layers, masks upon masks upon masks, a bewildering experience that is the literary equivalent of walking into a dark forest and never quite making it back out, or at least not making it back out quite the same.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Evan Reads to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.