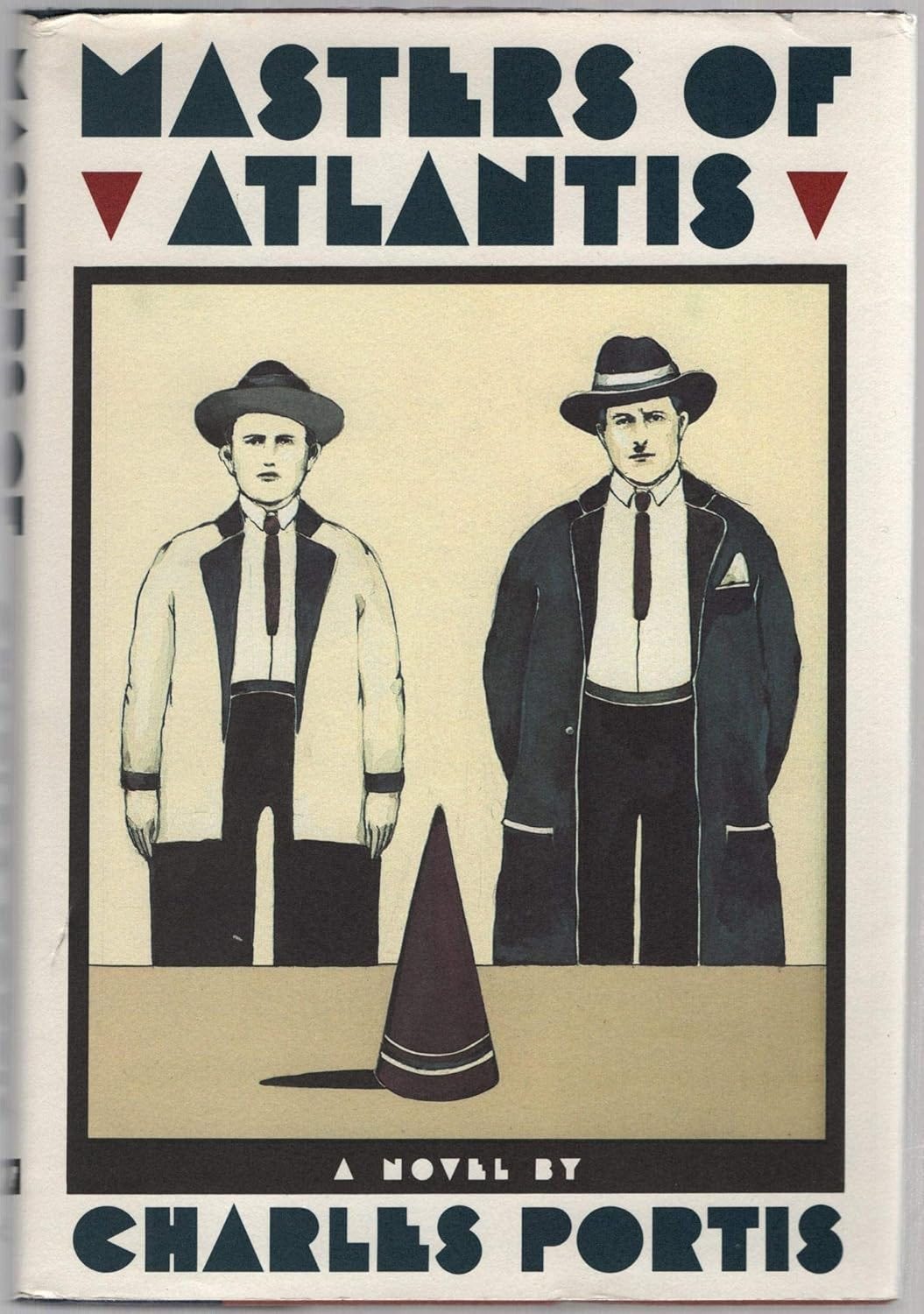

I’ve spent a lot of time here thinking about the beginnings of books, and have gone so far as to call the beginning paragraph of Charles Portis’s Dog of the South one of the best openings of all time, full stop. But forget a paragraph, or even a longer sentence, sometimes all you need are a couple words: A screaming comes across the sky. Call me Ishmael. Maman died today. And, in Portis’s 1985 novel Masters of Atlantis, this immediate call to action, these perfect first three words: “Young Lamar Jimmerson.” The sentence goes on, but I didn’t need any more than just that: Young Lamar Jimmerson. Lamar Jimmerson! Instant kill, you got me; it’s the clarion call for the kind of half-stupid half-genius humor I love. Fine, the sentence goes on, the book goes on: “Young Lamar Jimmerson went to France in 1917 with the American Expeditionary Forces, serving first with the Balloon Section, stumbling about in open fields holding one end of a long rope, and then later as a telephone switchboard operator at AEF headquarters in Chaumont. It was there on the banks of the Marne River that he first came to hear of the Gnomon Society.” Buonissimo. We’re off, Young Lamar Jimmerson in tow. (But god, the clause “stumbling about in open fields holding one end of a long rope” is perfect Portis – immediate summation of a totally guileless character tripping through the very real world.)

Masters of Atlantis has the shaggiest-dog plot of Portis’s already-quite-shaggy oeuvre. Where Norwood, True Grit, and Dog of the South all feature someone leaving home and then wending their way back, Masters of Atlantis orbits around Lamar Jimmerson, the Gnomon Society, and the mix of conmen and true believers that come to surround him over time. The Gnomons are an ancient secret society based off a book of teachings taken from the lost city of Atlantis; Pythagoras and Agrippa were apparently members, and the triangle is the key shape amid its gnomic teachings. The details are sketchy, since the person who tells Young Lamar Jimmerson about it changes his name four times after their first meeting – first he’s Nick from Turkey, then Mike from Egypt, then Jack, an Armenian from Damascus, and finally Robert, “a French Gypsy.” While stringing Lamar along for meals and shelter, Nick/Mike/Jack/Robert gives Lamar a small, untranslated Greek book, the Codex Pappus, named after the society’s mysterious leader Pletho Pappus (another excellent name.) All for the low price of 200 bucks (paid in advance), Jimmerson gets to hold onto the book with the promise of a ceremonial robe and 1,000 bucks a month “as soon as his name was formally entered onto the rolls.”

After being so successfully bilked, Young Lamar Jimmerson (I’ll never get tired of it) heads to Malta in search of ‘Robert’ and the Gnomons, enacting a kind of shithead’s version of Pynchon’s V., where even less is resolved. “He walked the streets looking at faces, looking for Robert, and clambered about on the rocky slopes surrounding the gray city that sometimes looked brown.” (Compare to ol’ Tommy P in V.: “It must be an alien passion in Malta where all history seemed simultaneously present, where all streets were strait with ghosts, where in a sea whose uneasy floor made and unmade islands every year this stone fish and Ghaudex and the rocks called Cumin-seed and Peppercorn had remained fixed realities since time out of mind.” Phew!) Near his lowest point, adrift in Malta, he finds a way to translate the Codex bit by bit, meets the young British aesthete Sydney Hen, and eventually two new chapters of the Gnomon Society are founded, Lamar taking it back to the States and Sydney heading to Canada. A kind of ridiculous schism forms between the two, and suddenly we have two ridiculous Gnomonic sects competing for the soul of North America.

Sydney, fussy, haughty, and competitive, is just one of the many funnily named figures that comes to surround the Gnomons, alongside Sydney’s sister and Lamar’s wife Fanny Hen, a man known just as Bates, a Mape, and Austin Popper, Morehead Moaler, Cezar Golescu, Pharris White, Maurice Babcock, an annoying couple named the Gluters for good measure, and many others; anecdotes about each of them spoke out as they dip into and out of the long winding road of the ‘plot.’ There’s not much there besides the (brief) rise of the Gnomons – who reside, at the height of their popularity, in a grand temple outside Gary, Indiana – and their long, long fall to a devoted few in a trailer park in Texas. Forward motion is not really the point here; it’s all about the spiral. (One of Lamar’s key Gnomic teachings is “The Jimmerson Spiral,” after all.) Digression and logorrheic flight are the name of the game, and everything is a setup to get these ridiculous characters bloviating.

The most ridiculous, most entertaining, and most bloviating of these characters is Austin Popper, a classic Portis-ian gabber a la Grady Fring in Norwood, Rooster Cogburn in True Grit, or Dr. Reo Symes in Dog of the South. An aggressive salesman / small time grifter, Popper pushes Gnomonism by dumbing it down for the masses and turning it into a kind of self-help cult of his own personality:

There was no shortage of idle men on Lake Erie but the wisdom of Atlantis, clarified through it now was, still did not hold their attention. Popper had to grope about for ideas they could hearken to. Little by little he worked things out. Most of the triangles and a good many of the oracular ambiguities had already been pruned from the Codex, and Popper went further yet. The Cone of Fate was not exactly abandoned but he no longer talked about it except in response to direct inquiry. The Gnomonic content of his lectures diminished daily as the Popper content swelled. Soon he had a coherent system, one with wide appeal, and he had to book ever larger rooms and halls to accommodate the growing number of men who came to hear his words of hope.

For this was what he gave them. Through Gnomonic thought and practices they could become happy, and very likely rich, and not later but sooner. They could learn how to harness secret powers, tap hidden reserves, plug in to the Telluric Currents. It was all true enough. Popper plugged them in to something of an electrical nature and he bucked them up with the example of his own dynamic personality and they went away thinking better of themselves.

All that “Popper content” – pure hot air. Once World War 2 breaks out, that “dynamic personality” dodges the draft, hightailing it from the Temple once a scorned ex-Gnomon Fed comes knocking. For the rest of the novel, on the lam, Popper loudly appears and disappears, always with a new scheme and a new story (and, fittingly for the Gnomons, a new name or two). (And, for a while, his talking bird, Squanto.) Even as Portis stacks a preposterous amount of jokes and bits per page, even competing against his distinctive narratorial voice and any number of excellent turns of phrase, the book is at its absolute peak when it locks into Popper’s distinctly American voice, the sheer sublimity of a conniving liar in top form, inventing and inventing as he wheedles on and on. There’s a scene late in the novel, on his return to the Temple after many years away, where he just uncorks a pages-long story about the particular contours of his time roughing it on the road back from alcoholism:

I jumped around a good deal. I tried my hand at real estate, selling beachfront lots out of an A-frame office in a patch of weeds. I sold used cars. ‘Strong motor.’ ‘Cold air.’ ‘Good rubber.’ Those were some of the claims I made for my cars, or ‘units,’ as we call them in the business. I bought fifty-weight motor oil by the case. Then for a time there I had a costume shop downtown. It was seven feet wide and a hundred and twenty feet deep and poorly lighted. My stock was army surplus stuff and little bellboy suits and Santa Claus suits and animal heads and rubber ears and such. I had more uniforms than Hermann Göring and sometimes for a bit of fun I would wear one myself out on the sidewalk to attract attention. Go through a few drill steps. ‘Jackets, bells and Luftwaffe shells!’ I cried. ‘While they last!’ Then I saw another opportunity and sold out to an Assyrian. They like to be on Main Street. The lighting is not a big thing with them. He beat me down on the price but I left a few surprises for Hassan in the inventory. That’s when I set up Bigg Dipper, a little operation dealing in oil and gas leases. Small potatoes, you understand, but my own show. That’s when I bought my motor home, which is not a luxury but an important business took. All this time things were coming back to me. No flood of light now, don’t get me wrong. I couldn’t arrange these events in consecutive way, and still can’t…

Besides the staccato, rhythmic quality of this monologue, and besides the roughly ten excellent jokes just packed into this small selection, Popper’s speech is built around diversion, a great flood of just one more thing, the ultimate distraction from the great absence of a man that hides behind this torrent. If we want to strain this novel to mean anything other than ‘enjoying a good yarn,’ it’s that we live in a country full of gabbling shysters just like this, that our national backbone is built on stories and who can tell the best one, or who can tell theirs the longest, and whatever ancient ideals we might start with – Atlantean, American – are diluted and eventually washed away by an onslaught of pure, self-serving drivel that is incessantly thrown at us.

But that’s some awfully serious stuff; the particular pleasure of any Portis novel is that this dark side coexists with an essential goofiness. Secret societies and their popularity across the American century might speak to a credulous population desperately seeking some kind of higher meaning, and speak to the sliminess of the people who take advantage of those disaffected yearners, but they’re also utterly silly, full of grown men (and yes, it’s always men) dressed up in costumes waving silly implements around in fake arcane rituals. This deep attention to the stupid makes Masters of Atlantis the ultimate hang-out book, swinging amiably from funny scene to funny scene. Trying to convey what’s funny is a mug’s game, but the sheer density of jokes and bits strung together in Masters of Atlantis is enough to make even the most po-faced readers crack. What can be conveyed are the exemplars of Portis’s style, his Twain-like eye for the absurdities of this American life. He describes a mailing list called “Odd Birds of Illinois and Indiana” as containing “the names of some seven hundred men who ordered strange merchandise through the mail, went to court often, wrote letters to the editor, wore unusual headgear, kept rooms that were filled with rocks or old newspaper. In short, independent thinkers, who might be more receptive to the Atlantean lore than the general run of men.” A confused Jimmerson asks an ice-cream man where the nearest public bathroom is, and receives the reply: “Probably at the zoo, said the ice-cream man, over that way. Over yonder. Out over in there.” Or this description of Popper on the run:

He made his way across the frozen surface of the Nasty River, here little more than a creek, its corruption locked up for the winter, and then up the Puerco Mountain, the talus giving way under his feet. When he rested he lay spread-eagled on the earth like a man holding on for dear life to a flying ball. He could feel no Telluric Currents flowing into his body. The mountain was dead. Near the peak was the main shaft of the mine called Old Woman No. 2. Inside he found a cranny he liked. […] One day they would put him away like this, with dirt in his mouth.

A man holding on for deal life to a flying ball! Old Woman No. 2! What else could you ask for? I could go on. I will go on! Of a boarder in the increasingly decrepit Gnomon Temple: “At no time did she attempt to pin Mr. Jimmerson’s ample hams against a tabletop, or touch him in a suggestive manner.” Ample hams! Like I said, sometimes it only takes a couple words to get you.

Does Masters of Atlantis have the winsome, sneaky emotional pull of Portis’s earlier books? Anything that matches Mattie Ross at the old Western show? Not really, though there is something oddly sweet about the dwindled assorted ranks of Gnomons – Adepts, Neophytes, and Masters alike – all together again on Christmas Eve in a Texas trailer park, keeping a very dim light going despite decades of adverse winds. But emotions, airtight plot, dynamic characters, all that’s overrated anyway; some jokes, the bunko outlines of an ancient society, a good hang, Young Lamar Jimmerson, that’s the good stuff.

You can get Masters of Atlantis at your local bookstore or local library. If you have to get it online, Bookshop.org supports independent bookstores across the country.

If you liked this post, please share it with a friend!