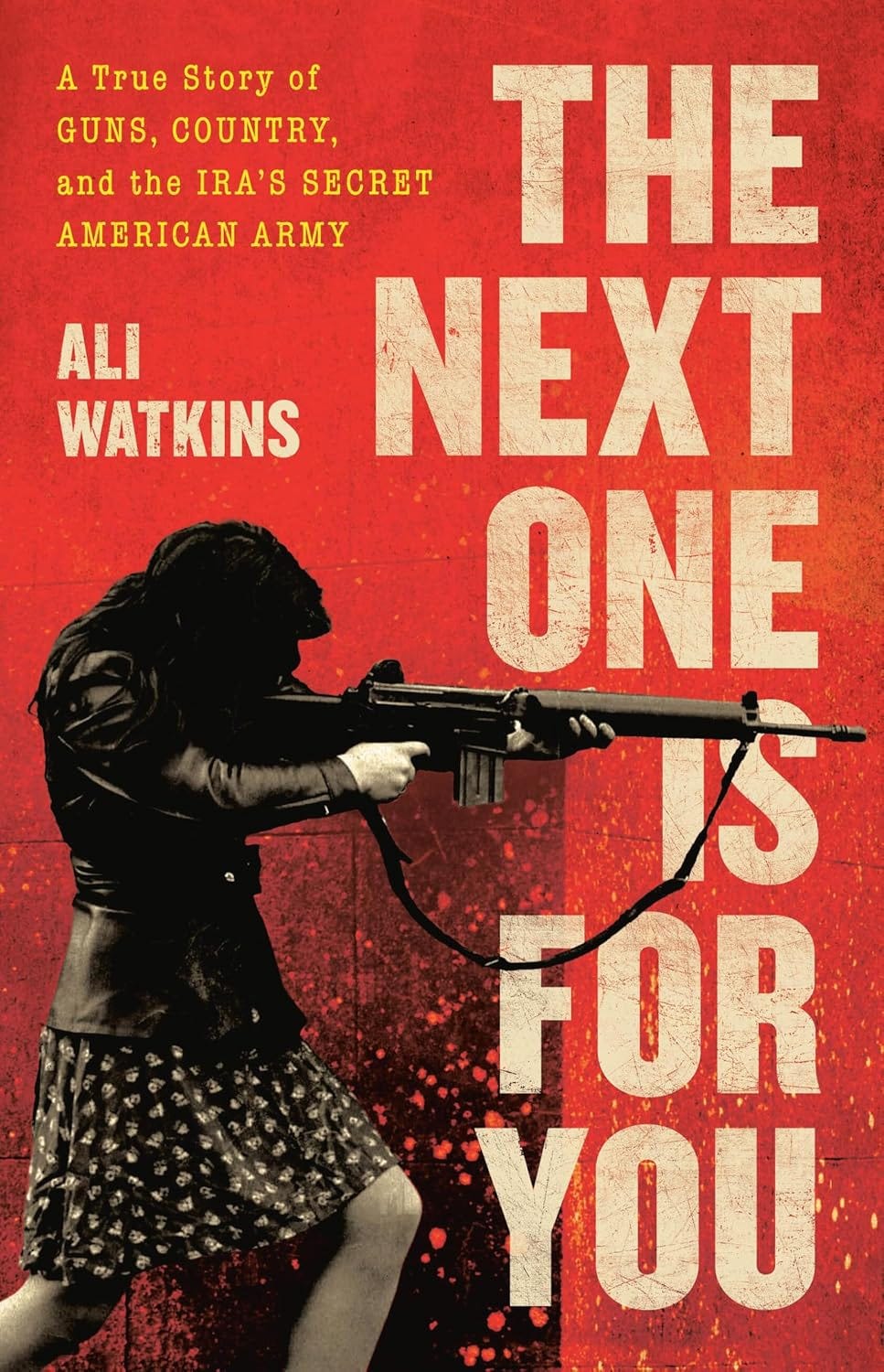

Most Irish-Americans are Republicans; the rest are Republicans. Despite the cavernous divide between American Republicanism and Irish Republicanism, the two have been surprising bedfellows: sometimes from a confused congressperson hearing the word "republican” and pledging their support for the Irish Republican Army, but more often from Irish-Americans unknowingly (or knowingly) donating money to the IRA via ambiguously-titled fundraisers. (I’ve been told the Irish side of my own family did so.) Besides that cannon of possibly misdirected money supporting jailed Provos’ families and giving IRA grunts their per diem, America, as it turns out, had another key export to the IRA: weapons. Amidst all this current talk of what this country manufactures, it’s easy to forget that America has been, nearly since its inception, one of the world’s foremost purveyors of arms, most of which get sold to various unsavory armies around the world. But there are times, once again unknowingly or knowingly, in which the sheer surplus of American guns means that some of them end up in the hands of movements that are not quite in line with the good ol’ American spirit, like, say, a bunch of balaclava’d Marxist revolutionaries fighting British soliders in Belfast during the Troubles. But how, you might be asking, how did all those guns get over to Ireland? Well, I’m glad you asked! Ali Watkins’ The Next One Is For You: A True Story of Guns, Country, and the IRA’s Secret Army is a deep dive into an Irish-American story that’s remained mostly under wraps over the past fifty years: a vast gunrunning ring that transported American Armalites across the sea to very willing Irish users.

Watkins’ subjects are a group of Irish emigres to America in the long aftermath of Irish partition; some of them are Northern Irish Catholics just looking for a fair shot at a job, a house, and family life in America, and others are on the lam after an IRA job or two gone wrong. (Even in the relatively quiet ‘50s and ‘60s, there were skirmishes across the Northern Irish border.) “Whatever the reason,” Watkins explains, “by the mid-twentieth century the steady flight of IRA veterans to America had effectively created a shadowy, satellite brigade of Irish Republicans within the country’s sprawling diaspora.” Philadelphia is the locus of Watkins’ study, and the city’s suburbs fostered a strong Irish-American population over the years, becoming “a harbor of sorts for Irish revolutionaries”; what began as simple Irish-American advocacy and community building turned increasingly radical as the situation in Northern Ireland worsened and the IRA became more militant. (Essentially, the switch from the dominance of the ‘Official IRA’ to the ‘Provisional IRA’ in the late ‘60s.) Whether ex-IRA or not, the tragedies of the early 70s - Bloody Sunday, mass internment, the Falls Curfew – energize the organizers back in the States, who increasingly yearn to find a way to help on the frontline. Guys like Vince Conlon – an ex-IRA soldier laying low in the States – and Danny Cahalane – an immigrant who gets exposed to more Northern Irish sentiment in Philly “than he ever [had] in Cork” – are just itching to turn their support into something tangible; the various group leaders’ differences in background are an indicator of just how wide-ranging the movement became in the US.

Out of groups like Clan-na-Gael (aka United Brotherhood, or Children of Ireland) and other local organizations comes NORAID (the Irish Northern Aid Committee), an organization that purported to support Irish Catholic families in Northern Ireland by working with another group in Belfast also called, you guessed it, NORAID. NORAID’s American chapters go to Irish-American events and pass the hat, playing off stoked tensions of the Troubles to raise more and more cash donations. Just one thing – that Irish version of NORAID is run by an IRA commandant, and a decent portion of the cash donations are going straight to the IRA rather than to struggling families. (Watkins is quick to note that much of the money did indeed go to the families; it’s just that, like any cash business, a lot of other money went under the table.) NORAID’s setup was key to an air of plausible deniability; the Provisional IRA needed “a fundraising mechanism that would tug at the hearts and purse strings of the Irish diaspora, without directly linking the money to the IRA,” and everyone involved on both sides of the ocean could simply, in classic IRA fashion, publicly deny that they were involved with the IRA. (Back to that twinned Republicanism: an American gripes that NORAID “wouldn’t dare bring any real Provos over here… All the Irish cops would hear one word out of their mouths and that would be the end of the contributions.”) But even with their money cannon set up, the more militant members of NORAID – the so-called “inner circle" of the organization, Conlon and Cahalane included – decided to go one step further and use NORAID cash to procure and smuggle weapons directly to the IRA.

Of course, another classic IRA thing is an alarming lack of operational secrecy, and so it’s not long before the American government catches wind of this scheme, with a little help from bewildered British intelligence officers pulling increasingly large weapons off the streets of Belfast. Through some complicated cross-ocean politicking – at one point, Watkins describes the US as “on every wrong side of a war of which it would have preferred to remain ignorant,” which is about as good a précis of US foreign policy as you can find – a federal case is eventually built against the so-called “Philadelphia Five” by the mid 1970s, strangling the supply of guns after thousands of them had made their way over the pond. (Enter one Mr. Gaddafi to make up for the shortfall after that.) Watkins’ reconstruction of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms’ case against the Philly Five is a light version of David Grann’s reconstruction of the FBI’s work in Killers of the Flower Moon, in that the ATF essentially established itself as a major law enforcement agency with this case, just as the FBI established itself as a major force with its work on the Osage murders.

But the focus in the book is, unerringly, on the robbers rather than the cops. Watkins not only gives the Philadelphia Five’s backstories, but also traces out their connections across the Eastern seaboard – New York is represented by the avuncular Marty Lyons, who greases all the right palms at the shipyard – and as many of their movements and purchases as possible. The book is full of backroom dealings in Irish bars up and down I-95, meetings in less than upright gun stores (dead Irishmen end up signing for a lot of guns), and a lot of suspicious packages marked as ‘plumbing materials’ socked away on an ocean liner, only to be dead dropped across the Northern Irish border. Escalation is the name of the game; when the cause is this urgent, the Five leave no stone unturned, including stealing from the US military itself; Watkins quotes a U.S. Navy report that “seven thousand guns and 1.2 million rounds of ammo were stolen between 1971 and 1974, much of it presumably secreted to Northern Ireland.” Like I said, there are so many guns here in the States that it’s easy to lose track of one or two or seven thousand.

In contrast to other narrative nonfiction accounts of the Troubles that have popped up over the past couple years – most notably Patrick Radden Keefe’s Say Nothing – Watkins does not center her story on a innocent caught in the crossfire of the Troubles in an attempt to counteract the book’s inherent interest in a militant revolutionary group. While not ignoring the IRA’s “ruthless tactics,” Watkins refuses to assign a moral valence to their actions and instead focuses on the realities of war, personified in this book by a young IRA soldier, Geraldine Crawford, who was shot while wielding an American gun, and then jailed for much of her youth because of this incident. (She never fired it herself, though who knows how many hands that gun passed through before it reacher her.) This singular incident is at once blessedly uncomplicated – this was a skirmish between two soldiers, one of whom doesn’t fire – but it’s also all that Watkins can find, specifically, linking an American gun to an IRA member, since the Northern Irish and British police were notoriously poor bookkeepers, and possibly too busy (or too careless) to always write down a gun’s serial number in their incident reports. Beside this one story, Watkins keeps her focus on the Americans, sprinkling in Irish anecdotes and clarifying history lessons only when necessary. The Americans believe in “the moral rightness of what they were doing,” and Watkins is careful not to put her finger on the scale either way with regards to that assertion; she may disapprove of violence, but shows a deep understanding of the conditions and events that led to the political use of violence. As Watkins writes of Crawford before that fateful night: “What else, then, was there to do?”

The Next One Is For You is longtime journalist Watkins’ first book, and there are times where the strain of keeping such a wide-ranging narrative organized is apparent; not that it’s easy to keep a bunch of similarly named Irishmen distinct in a readers’ mind, but Watkins sometimes doesn’t trust the reader enough, and certain descriptors and anecdotes get overused in order to reinforce who is who. But for the most part, Watkins is a steady hand on the till, receding into the background behind the story as all good nonfiction writers do. (It’s only in the epilogue that we learn of Watkins’ Irish-American Philadelphia upbringing and her own travails on the reporting trail, especially with regards to reaching out to Crawford, narratives that would dominate a different (and worse) kind of nonfiction book.) Most of the narrative sticks to documented facts, with sparing use of reconstructed dialogue, which saves the book from falling into ‘reading like a thriller,’ as some more luridly constructed true-crime books strive to do. That’s not to say it isn’t a compelling read – the long cat and mouse game between the ATF and NORAID is a bit like Goodfellas’ second half – but it’s just one that takes the truth more seriously than narrative convenience. No shortcuts here, no reckless assumptions, thank goodness.

As we approach 30 years of Good Friday Agreement brokered peace, there is simultaneously more and less information coming out from the Troubles: more records are being released every year, but more of the conflict’s participants are dying of old age, and it was already a tough thing to get people on the record about. (Blame the Boston College / Belfast Project debacle.) “The further we get from those awful, violent years, the more of those stories we lose,” Watkins laments in the book’s epilogue. “I’m not sure how one chooses what’s worth forgetting, but I do know this: peace is a difficult thing to find, without clear accountings of the past. The ambiguity of half-truths, perhaps, can be a more dangerous ending.” As much as Watkins’ book reveals, there is also a haunting sense of all the things we may never know for sure, either lost to time or put deep under wraps. That’s true of the IRA’s various inner workings – say nothin’ is still something of a national credo, and the British authorities aren’t willing to say much more of their work – but also, it seems, everything that was going in Irish America. There’s a throwaway line late in the book about a later case against NORAID that gets scuttled “thanks to evidence pointing to a bizarre CIA connection that the federal government couldn’t quite refute” which suggests another book’s worth of intrigue in itself; hopefully Watkins is the one to write it, or at least someone with her considerable journalistic skills. It’s the kind of work we need to get closer to that clear accounting of the past, even if the past’s ledger has never quite been on the up and up, just like any good cash business.

You can get The Next One Is For You at your local bookstore or local library. If you have to buy online, Bookshop.org supports independent bookstores across the country.

If you liked this post, please share it with a friend!

I presume Gerry Adams didn’t pen the Foreword?

Shout out to my Republican parents and grandparents, dressed for a fundraising gala. “But you’re Democrats”