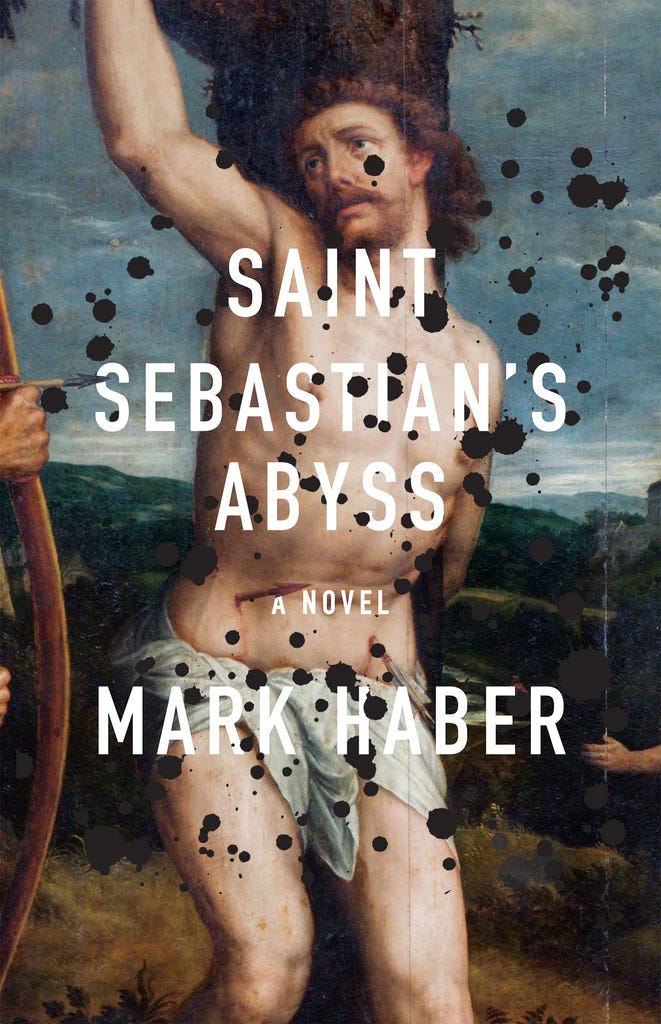

Actually Pretty Good: Saint Sebastian's Abyss

Mark Haber's novel puts art fanatics under the microscope

Most contemporary fiction is awful. Actually Pretty Good highlights new books that are, like the title says, Actually Pretty Good!

If there’s such thing as a writer’s writer, then I’ll propose a close cousin: the bookseller’s book. While customers usually expect booksellers to have read every single new book that’s come out in the past six months, most booksellers I know are instead reading obscure backlist titles or a galley from a little known press that they specifically asked a sales rep for. The common thread in these bookseller-loved books is a fundamental unsellability to anyone besides your fellow colleagues; these are books written by little known authors about sad or strange or sad and strange topics, and only the bravest of handsellers would try to pitch them in a line or two to just anyone.1 They’re often very short, so that one could, say, read it over the course of one particularly slow afternoon of business2, and which also makes them a tougher sell. (For as much as everyone says they want a short book, people generally prefer to buy bigger books - or even just bigger looking books - to justify spending their money. That’s why you’ll see short books sometimes released in, ahem, interesting bindings with wide page margins - there’s a certain page count the publisher is trying to get to.) They’re also often books about books themselves, or art, an obsessive literature for obsessives. Enrique Vila-Matas’ Montano’s Malady is a bookseller’s book (terminally well-read man confuses reality with literature), Bohumil Hrabal’s Too Loud a Solitude is a bookseller’s book (man in a basement pulps books, saves the ones he likes), Gerald Murnane’s The Plains is a bookseller’s book (man goes to the Australian interior and can’t make a film about it), Fleur Jaeggy’s These Possible Lives is a bookseller’s book (capsule biographies of English poets written in the least authoritative way possible), and César Aira has basically made a career out of bookseller’s books (they’re all novellas.)

With Saint Sebastian’s Abyss, we have a bookseller’s book in more than one way. Mark Haber is literally a bookseller, running the very fine Brazos Bookstore down in Houston. More crucially, it’s a book about two art critics who are obsessed with the painting of a little known Early Renaissance Dutch artist, building their friendship and careers off of their pure devotion to the titular painting, Count Hugo Beckenbauer’s Saint Sebastian’s Abyss.3 The narrator of the book is traveling to meet Schmidt, the other art critic, as Schmidt lies on his deathbed decades after a falling-out. Plotwise that’s just about all you get; the book is otherwise mostly just about the conversations that only two diehards can have, simultaneously the most and least important conversations in the world. To the people who care about an artist’s work, the small details mean the world; to the rest of the philistinic world, it’s nerds bickering over inanities. The arguments Schmidt and the narrator have about the painting, about their favorite parts of the work, over what it means, about how the artist’s lesser works pale in comparison to the masterpiece, are all akin to the talk behind the desk that you might hear at a record store (think High Fidelity) or, yes, a bookstore. A customer asks a simple question (What’s the best Replacements record?4 Which Dostoevsky should I start with?5) and is suddenly brought into the arcane world of small differences.

Haber also writes in a style popular among booksellers, using Thomas Bernhard-ian6 chapter long paragraphs full of unspooling sentences that double back on themselves, repeat certain phrases, and most of all work with a sort of feverish momentum. It’s not quite stream of consciousness; it is more like a record of anguish or something the narrator is impelled to explain by some devilish inspiration. The inspiration for the narrator here is the painting itself, and the primacy of all art, as well as a continuing competition with Schmidt. What starts as a sort of chummy collegial relationship centered around their love of the painting and their role in promoting it to the world – they initially each write the forewords to each other’s books – curdles into something more contentious after their falling-out, a critical schism opening between them, their books written only to refute the other’s latest, younger critics choosing sides between the two men and their theories on the painting. So while the narrator is nominally going to visit his old friend on his deathbed, his plane ride becomes a way to give an exhaustive account of their theories, the evolution of their theories, their friendship, and the breakdown of their friendship, and the longer sentence / fewer paragraphs style aids in that exhaustiveness - all of this MUST be understood, it seems to say. Ironically, the chapters themselves are extremely short, most only a page or two, an effect that heightens the perceived urgency of the text - you can almost imagine the narrator finishing a thought, ripping off a sheet from a notepad, and immediately going to the next thing that must be known.

In using words such as ‘anguish’ and ‘urgency’ I fear I am shortselling one of the book’s best qualities – its humor. Schmidt and the narrator are absurd characters, caricatures of art world snobs, and they delight in imposing their taste on others. The painting they’re obsessed with is only twelve inches by fourteen, and they both cup their eyes so as to only see the painting and not have any other art at the museum impose on them. Beckenbauer himself is a syphilitic, sex crazed madman, all the facts revealed about his life undercutting the sublime promise of the work. The way Schmidt and the narrator discuss the details of the painting are ludicrous, each of them ascribing every possible meaning to the painting, each maintaining that the painting includes and resolves its own tensions, each making overarching conclusions that can only come from sustained and singleminded focus. Take for example one of the narrator’s descriptions of the painting:

“Saint Sebastian’s Abyss, like all masterworks, contains multitudes. It’s drenched in color but entirely devoid of color. It’s not a landscape though it’s certainly pastoral. It’s not religious though it’s bursting with religious symbolism: apostles, iconography, the holy donkey, a sky rent by divine lightning. To try and describe Saint Sebastian’s Abyss in words is an act of futility, thus the allure Saint Sebastian’s Abyss held for a young Schmidt and me…”

This mode of criticism is a sort of academic mania where the chosen object of study can answer any question, where it relates to everything in the world, a mania fueled by what Schmidt fittingly refers to as “the inexhaustible superabundance of Saint Sebastian’s Abyss." If the act of writing about the painting is truly “an act of futility,” the two critics are all too eager to fail, and fail repeatedly, knights errant pledged to the painting. Both critics despise the only other two surviving paintings of Beckenbauer, which they derisively call “monkey paintings” when compared to their beloved Saint Sebastian’s Abyss. These paintings, to complete the punchline, are vastly bigger than Saint Sebastian’s Abyss, and hang on either side of it, and the critics enact a quite literal version of Manny Farber’s “White Elephant Art vs Termite Art” distinction in their devotion to the small, idiosyncratic work against the large, bombastic paintings. They’re both consumed by the idea of the end of the world, becoming something like a fatalist Statler and Waldorf, reading the apocalypse into every detail of the painting and considering anyone who isn’t obsessed with the world’s end as beneath them. Their snobbishness isn’t just a feature of their friendship; it’s inflicted on the world. Schmidt most famously maintains that no good art has been made after 1906, and in fact maintains that all art after Cezanne died is “trash,” and walks through museums clicking his tongue and coughing and telling patrons that they are looking at trash. It’s the best portrait of critics, and their sort of essential absurd patheticness, since the first part of Bolaño’s 2666.

The really funny thing, however, is that despite their insufferability, Schmidt and the narrator are – and I hate to use this word – relatable. Most everyone has something they care about more than anyone else in the world, and then they meet someone else who actually does care about that thing in the same way, and that’s when the best kinds of conversations begin, ones filled with hyperbole and ridiculous statements. When Schmidt says that no good art was made after 1906, and that the narrator’s second wife, a Klee scholar, has wasted her life “studying garbage,” the laugh comes with a wince of recognition. I wince because I’m the guy who’s thrown these out into the world: the novel as a form peaked in the 19th century, and essentially died when propriety went out the window. “Swingin’ Party” is the best song ever written. Slanted and Enchanted is better than Crooked Rain, Crooked Rain. The 2005-06 Buffalo Sabres are the best hockey team of all time, despite and perhaps because they didn’t win a championship. Dostoevsky’s Idiot is a huge shaggy mess of a book with some of the worst structuring I’ve ever encountered and is a perfect novel.7 I don’t even believe half of those things, or maybe not fully, but I’ve thought so much about them that they feel true, or at least I’d argue with a friend about it, and we’d respect each other throughout that argument because of our shared fixation. That respect – or, alternatively, shared delusion – is the bedrock of Schmidt and the narrator’s friendship before something appropriately petty comes between them, what Schmidt calls “that horrible thing.” The break between the two is absurd, predicated on an escalating snobbishness, and it couldn’t be any other way.

These two characters care deeply about Saint Sebastian’s Abyss, and on a higher level, the power of art, even if it’s to a ridiculous degree. Their passion is a refreshment next to the sort of ironically distanced, anomic autofiction narrator that dominates a lot of contemporary fiction. I couldn’t help thinking8 of Ben Lerner’s Leaving the Atocha Station, the novel that first catapulted Lerner to literary fame. The narrator of that book – Lerner’s stand in for himself, Adam Gordon – goes every morning to an art museum, and one day sees a man break down and cry in front of a painting. Gordon can’t match that man’s “profound experience of art” and worries that he’s actually incapable of having such an experience, and that sets the tone for the novel, which insistently questions how much a person can actually connect with the epiphanic promise of art. In contrast, Schmidt and the narrator stand in front of Saint Sebastian’s Abyss and weep, sometimes have to leave the room in order not to be “overcome by emotion,” they ruin their lives for their love of the work and, yes, they cup their eyes and look quite silly in order to see only the painting. While I can’t imagine enjoying spending a ton of time with either Gordon or the critics, I know who I’d rather have a drink with, because in fact I’ve had drinks with both of these types, and give me the overwhelming passion over the jaundiced near-nihilist cynicism, give me late night conversations about how someone’s worst book is actually their most fascinating and must be read in order to even comprehend their best ones, give me dying on a hill that anyone else would call a molehill. It’s only art, and as every record store clerk, film critic, and bookseller knows, it’s absolutely everything to the right people.

You can buy Saint Sebastian’s Abyss from your local bookstore, check it out from your local library, or order it from Bookshop.org, where every purchase supports local booksellers across the country. Buying from Bookshop.org also helps support the newsletter through their affiliate program.

If you liked this newsletter, please share it with a friend!

Instead, your very brave correspondent will try to sell you on this book over what Substack estimates to be fifteen minutes of speaking time, at which point most customers would be edging towards the door.

Hypothetically speaking!

The painting and the painter are not real, though there’s plenty of real art mentioned throughout, and the painting hangs in a real museum.

It’s Tim!

Probably Notes From Underground or Crime & Punishment.

And László Krasznahorkai-an, and Sorrentino-ian, and early Bolaño-an style, all incidentally authors who write a lot of bookseller’s books. Bernhard’s Correction is like a book length advertisement for suicide, and thus a pretty tough sell.

Even though I’ve said perfect novels don’t exist, The Idiot is perfect.

I’m almost certain Haber had this in mind while writing the book, and other reviewers have also made this connection, including Jackson Arn in the Times.

Damn dude, this one hit me! I feeeeeel this, and the constant replacement refs make it even easier to relate to cause I must have had a hundred light night/early morning rambling convos with friends and strangers about the merits of Don’t Tell A Soul and why Achin’ To Be is maybe their best . . . I don’t miss the hangovers tho!