An EvanReads Halloween Spooktacular

All the best creepy, crawly, and eerie literary fiction for your scary season

The air is crisp… the days are getting shorter… the leaves are turning … one of the many weird sequels to Halloween is on TV at all times, but never the original… that’s right, it’s Halloween season, so why not grab a suitably creepy book or two for your next couple weeks of reading. If it’s relatively rare for a book to make someone actually laugh out loud, someone being legitimately frightened by a novel is that much rarer. While a couple great books have made me laugh – Hasek, Svevo, Portis and Joy Williams are probably my favorite funny writers – or even let out a dry chuckle – Proust is great for a chortle here and there – never has a book made me recoil in fear or scream. Film has the definite advantage here; there’s nothing a book can do that works quite like a jump scare, and the visceral reaction to seeing someone run towards you with a chainsaw is much stronger than reading about it.1What literature can do on or above the level of film, though, is create a sense of dread, a growing unease that’s fed by one’s imagination. Movies are typically less scary once you see the monster; a novel can give you enough suggestive detail to put a pit in your stomach long after you close the book.

I don’t read a ton of ‘straight’ horror, but I have found that a lot of my favorite literary fiction (or what we’re no longer calling literary fiction – it’s art fiction now I guess?) takes on elements of horror and the gothic in order to reach its affective goal. So for now I’ll skip the classics of the horror genre – Henry James’ Turn of the Screw, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Edgar Allan Poe’s stories, Shirley Jackson’s entire oeuvre – and the contemporary masters of horror like Brian Evenson to instead focus on some fiction that takes on horror in a slantwise way. Read on, if you dare….

Pew, Catherine Lacey

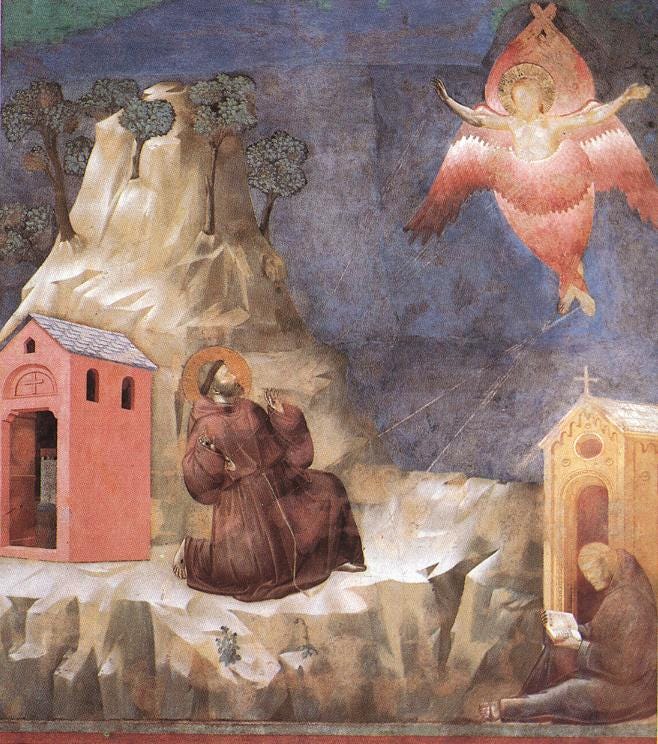

Devoted readers will know that I did not particularly love Lacey’s latest novel, The Book of X, but her previous novel, Pew, is something like the literary version of the ‘biblically accurate angels’ meme. A stranger arrives in an even stranger town and is taken in by a vaguely menacing church, passed from house to house as a silent presence to receive off-putting monologues. (As I’ve said before, Pew takes the Rachel Cusk novel formula and freaks it.) Eeriest of all is that Pew, as the townspeople begin to call them, does not seem to have any fixed form; they appear to whoever’s looking at them as a sort of personalized version of the Other, ambiguously raced and gendered. Taking place over one week, never has a church Sunday loomed quite so ominously. It’s LeGuin from another angle, quick, creepy, and a quality read.

Pedro Páramo, Juan Rulfo (translated by Margaret Sayers Peden)

Susan Sontag calls this novella a “multivoiced sojourn in hell.” Compelled by his dying mother to seek out his father, Juan Precadio arrives in the small town of Comala to find only a ghost town. “It doesn’t just look like no one lives here,” he’s warned – “No one does live here.” So it is in this surreal little gem, as Precadio meets a host of spirits, disembodied voices, and hallucinatory visions of the past, all tracing out the true story of his father and his legacy in the town. There’s no magical realism and no Garcia Marquez without Rulfo, but his has a more sinister bent to it; once you get to Comala, you can’t really leave.

Hurricane Season, Fernanda Melchor (translated by Sophie Hughes)

You wanna see a dead body? So begins Hurricane Season, as five boys in a small Mexican village come upon “the rotten face of a corpse floating among the rushes and the plastic bags swept in from the road on the breeze, the dark mask seething under a myriad of black snakes, smiling.” It’s the body of “the Witch,” and the rest of the novel, told in entrancing chapter-long paragraph monologues, establishes the Witch as either a misunderstood caretaker with feminine mystique or an actually spiritually malignant force. Otherworldly or no, there is something certifiably evil happening in the village, a malfeasance practically seeping from the walls; at a certain point it seems as if an evil demonic presence has even taken over the narration of the book itself. A profoundly disquieting catalogue of miseries. Isn’t that what you wanted?

Eileen, Ottessa Moshfegh

The literary community seems pretty tired of Ottessa Moshfegh’s grossout-shtick at this point; alternatively, the popularity of My Year of Rest and Relaxation made it acceptable for the knives to come out. All that being said, Eileen, the book that initially launched Moshfegh, is a concise and luridly entertaining piece of gothic macabre. It starts off merely gross – Eileen is the secretary at a boy’s prison and her alcoholic father’s caretaker, and in both roles the subject to a growing pile of indignities – before the arrival of the beautiful Rebecca Saint John at the prison tips the story into more outright perversity. If you haven’t read it yet, finish it before the movie comes out in December; that way you won’t get overwhelmed by the torrent of thinkpieces it elicits.

The Changeling, Joy Williams

Already much-covered in this space, though I wouldn’t ever miss a chance to mention it again. A true grim and gothic fairy tale, in the vein of the real fairy tales before they got cleaned up and Disneyfied. To put it another way, Beauty and the Beast but the Beauty is always drunk, she’s a prisoner of her terrifying in-laws on a scary island in New England, and the beast(s) may possibly end up in control by the end. (Imagine Belle turning into a Beast rather than its opposite at the end of the flick.) Alternatively, the book is about just the pure terror of mothering a newborn; for a lighter and even more horror influenced take, see Rachel Yoder’s Nightbitch, which welds new motherhood to a werewolf story.

The Book of Night Women, Marlon James

In a similar vein to Toni Morrison’s Beloved, which engaged the legacy of slavery through a haunted house story, The Book of Night Women puts the telekinetic powers of Carrie or Scanners into the story of a Jamaican slave revolt. It has all the postcolonial verve of James’ other work – shifting lines of power and desire between oppressor and oppressed, alteric visions of femininity and might, and wide-ranging narrative voices in a number of different registers – while also featuring gory psychic abilities and more than a couple exploded heads and slashed arteries, perpetrated violence rebounding on itself.

Satantango, Laszlo Krasznahorkai (translated by George Szirtes)

Pure dread from the start, with its first narrator, within the novel’s first pages, in thrall to a vision of extreme human misery and cosmic insignificance:

He gazed sadly at the threatening sky, at the burned-out remains of a locust-plagued summer, and suddenly saw on the twig of an acacia, as in a vision, the progress of spring, summer, fall, and winter, as if the whole of time were a frivolous interlude in the much greater spaces of eternity, a brilliant conjuring trick to produce something apparently orderly out of chaos, to establish a vantage point from which chance might begin to look like necessity… and he saw himself nailed to the cross of his own cradle and coffin, painfully trying to ear his body away, only, eventually to deliver himself – utterly naked, without identifying mark, stripped down to essentials – into the care of the people whose duty it was to wash the corpses, people obeying an order snapped out in the dry air against a background loud with torturers and flayers of skin, where he was obliged to regard the human condition without a trace of pity, without a single possibility of any way back to life, because by then he would know for certain that all his life he had been playing with cheaters who had marked the cards and who would, in the end, strip him even of his last means of defense, of that hope of someday finding his way back home.

Ahhhh!!!! From there, we see the breakup of a collective farm in post-Soviet Hungary, with the arrival of a huckster who might be the devil himself, a long party scene that reads like a grotesque parody of those long party scenes from Proust, and a bravura section about a little girl in successive and sometimes simultaneous contact with the depraved and the transcendent, and an all time freak-out ending that I wouldn’t dare spoil. So come on in, join the dance!

NB: The Bela Tarr film version of Satantango is a crisp seven hours if you want to gather some freaks for a fun day of durational cinema and change up your usual Halloween movie rotation. Both the book and film are masterpieces of their respective forms.

Autobiography of Red, Anne Carson

The terrors of queer intimacy!!! This novel in verse follows Geryon, “a monster everything about him was red” with wings, known from mythology as one of the victims of Hercules’ 12 labors. (A monster variously described as having many legs and/or arms and/or heads, he had his famed cattle taken by Hercules, and was shot and killed by an arrow in the process.) Carson refashions the mythological story from one of physical violence to a more emotional violence, as Herakles arrives on Geryon’s red island and steals Geryon’s heart instead. Verbally dextrous and endlessly inventive, it’s a book that ought to be in the monster book canon alongside Frankenstein, even if it simply recasts monstrousness as a metaphor for adolescent self-shame and the feelings of unrequited love.

Ghost Wall, Sarah Moss

All the lurid horrors of British antiquity found in The Wicker Man yoked to a grim family vacation, with a splash of Midsommar’s feminist slant. Silvie, a high schooler, is on an anthropological field trip with her mother and father, reenacting the way of life of the Iron Age Britons alongside some university students. While the students have an academic interest in the way things were back then, Silvie’s father is in it for the love of the game, so to speak, and his zeal for ‘authentically’ living like an ancient – including the institution of a retrograde patriarchal rule – begins to infect the rest of the camp. I probably don’t need to say much more than “ancient ritual reenactment” for you to get where things are headed, but Moss’s book has enough strange particularities, and enough ambiguity, to support multiple readings (Brexit-era political, feminist, etc) and encourage re-reads. What’s more ‘Halloween-y’ than ancient druid stuff, cmon!

Hopefully one or two of those scratches the itch for you; if not, well, I’m sure Halloween H20 or Friday the 13th Part VIII: Jason Takes Manhattan is currently on TV for you. Maybe you can read one of these books on something as cool as the shell e-reader from It Follows, an excellent horror movie:

If only we could be so lucky! Let me know if I missed anything in the comments.

Thank you to subscribers Anthony M. and Brendan B. for the long-term inspiration for this piece - both asked for horror recommendations, which got me thinking more on the subject. Paid subscribers can always ask for recommendations and commission pieces - so why not sign up today!

I was once at a haunted maze and saw an actor jump out and scare the people in front of us with a chainsaw, and then still got scared when he jumped out at us a minute later.

I'll nominate two in the "dread" more than "fright" category: Dorothy B. Hughes' "In a Lonely Place," about a serial killer in LA and "Lolly Willows" by Sylvia Townsend Warner, about a resolutely single woman who becomes a witch.

I nominate Benito Cereno for conjuring a sense of dread . . . But does that get ruled out with Poe and Frankenstein etc?