I’ve said it, Vivian Gornick’s said it, and Elizabeth Hardwick’s said it, so who else do you need to hear from? The end of propriety means the end of the novel, or at least of a certain very prominent strain of it.1If you think back to the novels of Hardy, Flaubert, Wharton, James, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, all those hoary greats of what we might consider the peak of the novel, they all have adultery (premarital or otherwise) foregrounding or at least underpinning the drama of their novels. If someone - usually a woman’s - indiscretion is discovered, their life will be ruined; society will shun them, and their life is for all intents and purposes finished. Those are real stakes, and those stakes disappeared as the twentieth century and modernity marched on, religion becoming less entrenched and women becoming more sexually free. Premarital sex? Not as big a deal. An affair? Make like a Frenchman and just move on. Maybe a marriage would end, but certainly not a life! Sorry to Emma Bovary and Lily Bart – women caught in the wrong era.

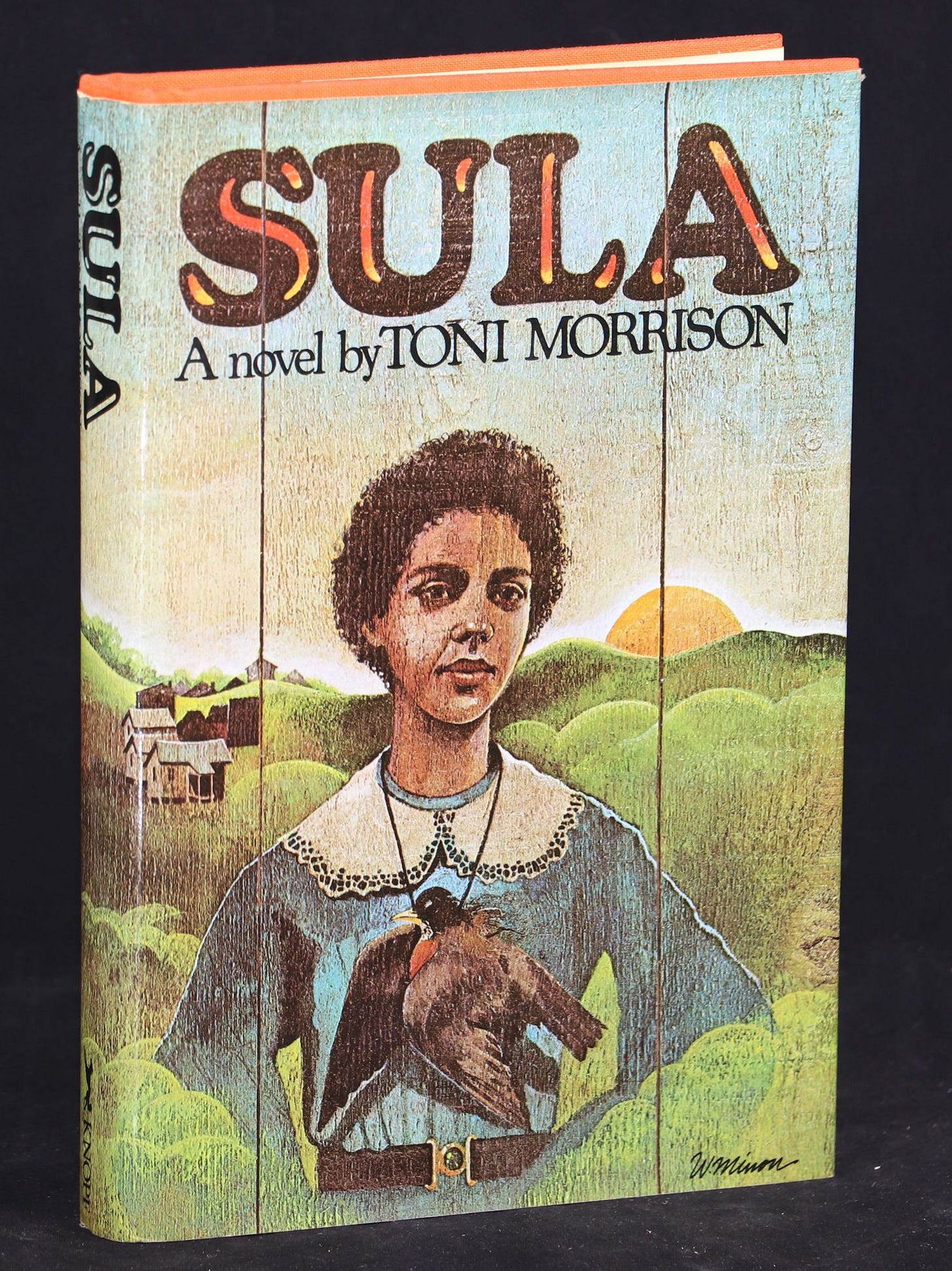

Those circumstances made for some tough sledding for realist writers in the 20th century – how to keep a novel realistic and interesting without those stakes? The lurid escalations of the midcentury – Updike in Rabbit, Run and Yates in Revolutionary Road and the stories of Cheever and O’Hara – showed one path, while other writers took different tacks, the postmodernists broadly abandoning the novel of love (or at least the straightforward one) while others wallowed in its discontent. I’m thinking of fiction like Alice Munro’s many stories of people breaking up and making up or never seeing each other again and living strangely normal lives after that, but also of novels like Toni Morrison’s Sula, which saw that the novel of propriety is over and says: so what? Did it ever matter? Any of it?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Evan Reads to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.