Discourse Court: Writers Reading

Dive into the morass of Literary Twitter as the Discourse Course makes its first ruling

Discourse Court: I’ll put on the judge’s robes and make a ruling on whatever stupid thing everyone’s talking about on the literary internet. The court will not allow for any hedging or dialectical answers.

All Rise!

Honorable Justice Evan C. Dent presiding; Hon. Justice Winnie consulting.

Today’s case: Do writers have to read books?

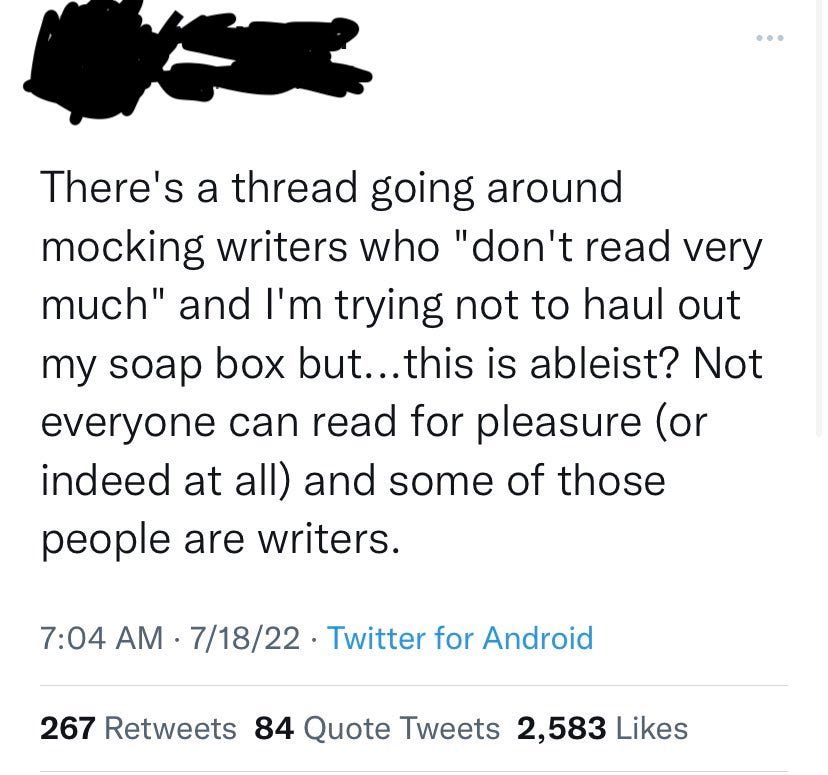

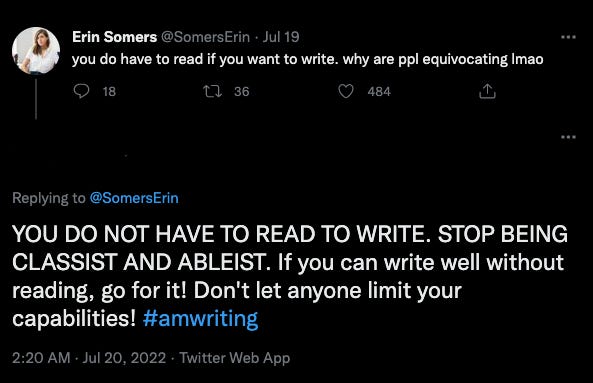

Defendants and Prosecutors: Honestly I cannot find who started this argument. The tweet that seemed to incite the discourse is screenshotted below, but I can’t find the thread that this person is referring to:

I believe the initial thread was making fun of Young Adult (YA) authors for not reading very much, but investigations have thus far been inconclusive. The true origin of Discourse is always obscured, but this idea probably entered the wider literary sphere recently when the author of an upcoming YA retelling of The Odyssey admitted that they had never actually read The Odyssey. The prosecutors in this case ended up being most of the working writers on Twitter riffing on the above screenshotted tweet.

Court Decision: First, some background for the Discourse Court. I got this idea mostly from just experiencing the onslaught of what we might call ‘Literary Twitter’ every day. I work at a bookstore, and the Twitter account for the store was set up years ago, and I don’t know who decided to follow most of the people on there, but it pulls in way more of the literary world than I choose to follow on my personal account. Just by logging on at work (nominally to post for us and/or see if anyone’s said something nice about us, but mostly to kill time), I am subjected to whatever ‘Literary Twitter’ wants to talk about that day. Now, in an ideal world, and with the right accounts followed, and with judicious use of the block and mute functions, ‘Literary Twitter’ would be a nice place where people talked about books they’re reading, books they’re excited to read, events they want to go to, or just sharing nice passages from books. And sometimes you even do get that! Here’s a nice thread of people talking about “quiet books” that my mom sent me:

(To make this post even somewhat worthwhile, I will here suggest Marilynne Robinson’s Housekeeping and Gilead, Yiyun Li’s Where Reasons End, William Maxwell’s So Long, See You Tomorrow, Evan S. Connell’s Mrs. Bridge, and the afore-reviewed John Williams’ Stoner as good quiet novels.)

It’s just that more people want to talk about the stupid things they see than the interesting things. The initial appeal of Twitter was that it democratized access to famous people’s opinions, and the utopian ideal of ‘Literary Twitter’ is that you could follow a writer you like and get their unvarnished thoughts sent right to your phone. Instead what you get is a site full of people playing the world’s worst game of show and tell and arguing about a revolving set of issues: is getting an MFA worth it? Should [Insert Writer] be cancelled? Is liking [Insert Writer]1 a ‘red flag’? Do audiobooks count as reading? Can you separate the art from the artist? Do authors actually believe and endorse everything they write in a book? Is [classic canonzied text] actually bad, and not worth reading? And did you see what [Insert Famous Author]2 tweeted?

These are the consistent fights that pop up every two weeks on ‘Literary Twitter,’ and the Discourse Court is meant to settle them once and for all when they appear again, stopping those lonely tumbleweeds from making another trip around the world once and for all. This question, though – do writers have to read to write? – appears so transparently stupid and obviously answered that the Court never even thought they’d have to address it. That’s settled law, and only clown courts would go ahead and mess with that. However, the one true maxim of the internet is that no matter how outlandish an opinion, someone out there truly and genuinely holds it. And not only will they have that opinion, but they will also give their life to defend it. And so we’re here: do writers have to read books to write?

Let’s first off dispense with the ‘ableism’ theory of not needing to read in order to write; if for whatever reason you cannot read a book, there are audiobooks and books in braille and all sort of other ways to read a book. The argument is that it’s ‘classist’ can similarly be brushed aside. Not everyone can afford books, and many people have work and care schedules that, I guess, could make it impossible for them to read, though I don’t really understand how they’d have the time to write in that case. There are public libraries out there, however, where you can rent a book for free, and I do think you can read on your commute or listen to an audiobook in your car if you have to drive, and you can at least make ten minutes for yourself when you wake up or before bed to read a little. But then some people might not have access to a local libr- wait, no: if you start seriously engaging with these lines of argument you end up down an ever more narrow path, trapped in hell, until an exception can be made for everything. Go to the library, or use an e-library. Read when you can. You do actually have to put in some work.3

Work: that’s the key thing here. Being a writer of any quality involves plenty of work this not, strictly speaking, writing. Researching, pitching, amateur tax accounting, revising, starting and maintaining a fledgling Substack newsletter, and a bunch of other things - including, most crucially, reading - are all under the umbrella, no matter how much you protest. The writing is supposed to be the best part, and the one you might want to spend the most time doing, but stubbornly insisting on only writing won’t make the rest go away. 4

But let’s focus on the importance of reading, specifically: If you want to be a good writer, you gotta read. Even if you hate every single thing you read, that still helps you as a writer, even if just as negative examples. You can say I don’t want to do that! and fling the book aside if you want, and you’ll still have something in your head to consciously avoid. On the other pole, reading good books, or books that sound similar to the thing you’re working on, is tremendously edifying. It gives you the opportunity to see how a problem is solved, the different ways in which the structure you’re trying to make can be completed. In short, you have to know which way the river is flowing before you step in - whether you’re going to paddle against the current or go with the flow. I don’t even mean that in a strictly commercial sense, but it is true that you do need to know, if you ever want to be published, what your work is similar to and what it is not similar to, and that it’s not too similar to something else out there. And finally, reading is exhortative: I find it hard to believe someone could want to start writing without ever having read a book, and reading enough good books will raise your own internal bar for quality - why write at all if not to reach for the heights?5

That’s all very utilitarian advice; really, you should read because it’s enjoyable, and it makes you a generally more well-rounded and intelligent person. (I’m not going to address ‘reading fiction as empathy generator’ until that case is inevitably brought to the Court). Getting sucked into this argument is actually really profoundly depressing; for one, it makes me have to justify art, when art needs no argument for itself besides the act of experiencing it. Even worse, it reminds me of all the people I’ve met in the real life ‘literary world’ who are just not at all interested in reading, or in literature at all.6 There was the guy in my MFA program who thought it interesting that I used the word ‘art’ to describe books - while he was finishing the second year of his Master of Fine Arts degree. There were the people in my MFA program who resented any part of the program that wasn’t the writing workshop, particularly being made to read Pynchon or Proust or anything ‘difficult.’ There are the bookstore customers who pretend they can’t read a sign that says ‘masks required.’ (More seriously, there are customers who just want to buy a set of books to decorate their house, with spine colors the most important factor, or who just want to take photos in front of the shelves.) There are the heads of publishing houses who care more about a book’s potential sales than its quality, and university heads who want to bring in more paying customers than produce good artists. It brings to mind what Enrique Vila-Matas calls in his book Montano’s Malady “haughty illiterates, managing directors of publishers that give shape to the black bottom of Nothingness.”7 When Vila-Matas says illiterate, he means something more like the anti-literate, those who get in the system and destroy it from the inside. Not to get all They Live on you, but they’re out there, and not just on Twitter! Small potatoes when compared to the ascending horrors of living in this world today, but the crass commercialization and commiserate deadening of literary culture is not a great thing to watch.

There’s no great way to wrap up a case such as this; you end up in the unenviable position of advocating for literature itself. One ought to read, and one must if they want to write, even if only for themselves. I’ll leave it to Vila-Matas in Montano’s Malady, an excellent book for booklovers everywhere:

“[I] begin not to understand why I must advocate reading. Let every illiterate in this country do what he wants … I spend the day planting mental bombs against all those businessmen who publish books, those departmental managers, market directors on the wire, and economics graduates … I wonder why I should lend them a hand and recommend they read books if I only wish them ill … I should advocate reading, albeit only in a stylized way by saying, for example, that there’s nothing to say, except that, without literature, life has no meaning. But, of course, I can only convince those who read of this.”

Judgement: Writers must read, and we plant mental bombs against anyone who says otherwise.

It’s David Foster Wallace.

It’s Margaret Atwood or Joyce Carol Oates. (Joyce Carol Oates - aka Joyce B. Tweeting - has given us the most disgusting picture of a human foot ever tweeted, and also the ‘wan little husks’ tweet. She has the range!)

This is par for the internet course, but what we’re dealing with here is the usage of social justice terms that have real meaning and real applications to mask an intellectual vacuity and laziness.

The idea of the nonreading author is like a fascinating tabula rasa thought experiment: would a writer exposed to no other writing produce something never before seen in literature, a narrative unbound from all literary convention? Would they eventually pump out Don Quixote like an unwitting Pierre Menard? Or just pump out some crappy YA fiction?

Feel free to own me here and note that this piece of writing is definitely not reaching any kind of height.

There are plenty of people I’ve met and even befriended who are not big readers; that’s fine, everyone has their hobbies, I’ll put up with yours and you’ll just have to put up with mine.

Ironically enough, it looks as though Montano’s Malady is being shipped from New Directions to an even more obscure and artistically focused publisher - Dalkey Archive!

Killing it Evan! Loved this one - except note #5 made me sad. There’s no need to try and make this essay anything more than what it is, but for what it is (a short essay) it’s fantastic! Don’t qualify yourself for anyone and keep reaching for the heights. Lastly I’ll say that, whether this disturbs you or not, there are certain sentiments in here that run parallel or at least remind me of stuff I’ve read from . . . Duh duh DUH, you guess it! Harold Bloom! Although in your favor, your ideas are more cogently expressed, more elegant by way of simplicity than Bloom . . . Keep it up bruv!

Cannot imagine a life without reading. As a writer, I learn from good and bad writing. Twitter is a rabbit hole….