Furious Vexations

On Kyle Buchanan's "Blood, Sweat & Chrome: The Wild and True Story of Mad Max: Fury Road" and George Miller's "Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga"

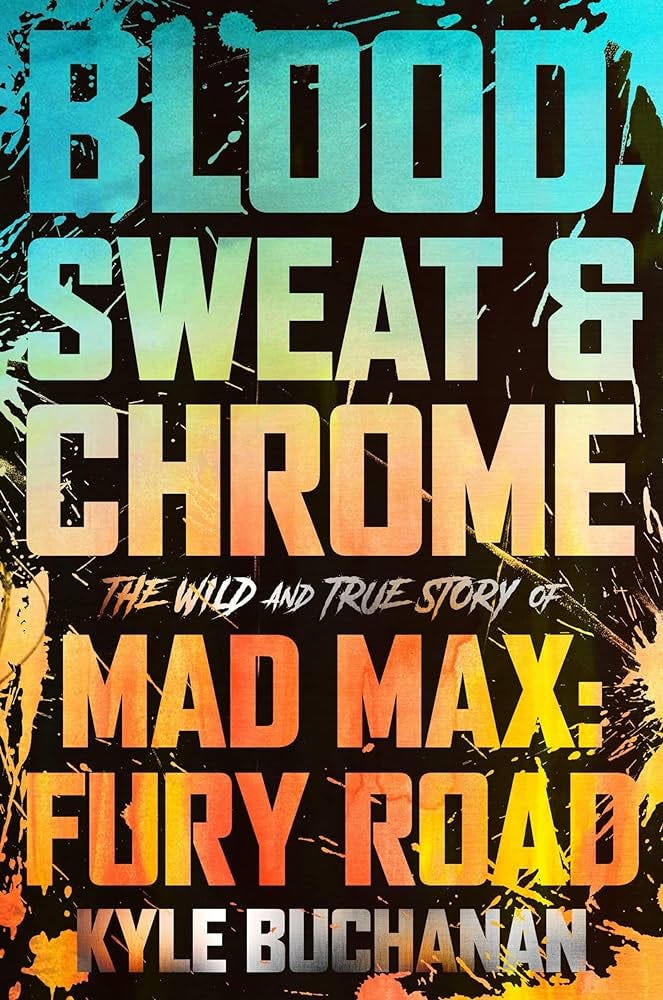

Following up 2015’s Mad Max: Fury Road is a near-impossible task; the film itself is a once in a lifetime achievement, a unique vision brought from one man’s head to the screen over the course of decades, a stunning document of sustained tension and pacing. But even beyond how terrifyingly good the movie is, the process of making it was so difficult that it seems ludicrous that anyone would sign up to do it all over again, as if you got Werner Herzog and Klaus Kinski in a room and said: “let’s go ahead with Fit2carraldo: Back Over The Mountain.” The story of the making of Fury Road – of which Steven Soderbergh famously quipped, “I don’t understand how they’re still not shooting that film, and I don’t understand how hundreds of people aren’t dead.” – is mythic enough to sustain its own oral history (Kyle Buchanan’s 2022 book Blood, Sweat & Chrome: The Wild and True Story of Mad Max: Fury Road) and also casts a shadow over its’ prequel, 2024’s Furiosa: A Mad Max Story, which, among its many thematic attentions to origins and mythmaking, pays particular attention to the difficulties of various productions within its post-apocalyptic landscape. Director George Miller actually had the monstrous War Rigs and muscle car contraptions built by found-object artists during the making of Fury Road; in Furiosa, we see the War Boys at work creating a War Rig, with one character instructing them that they will turn forgotten scrap metal and car pieces into a piece of found art, a fearsome machine custom-built for battle on the road yet still featuring detailed engravings and insignias of their leader on it, as if they had tipped Trajan’s Column over on its side, strapped it to a mack truck, and placed a bunch of medieval flairs on the back. In getting looks at the various strongholds of the Wasteland – Gas Town and the Bullet Farm, hinted at in Fury Road, and now seen, in the somewhat clunky way that prequels will do, as fully realized places in Furiosa – we see legions of workers just behind the main characters, at once a teeming and faceless underclass but also essential to the world’s continuance. Miller knows how essential his crew is to his films, and this is a film that, between ludicrous practical stunt filled car battles, attempts to honor and highlight their backbreaking work. The lingering question in Buchanan’s book, and maybe unconsciously over Miller’s two movies, is: are they “great despite being forged in fire, or because of it?”

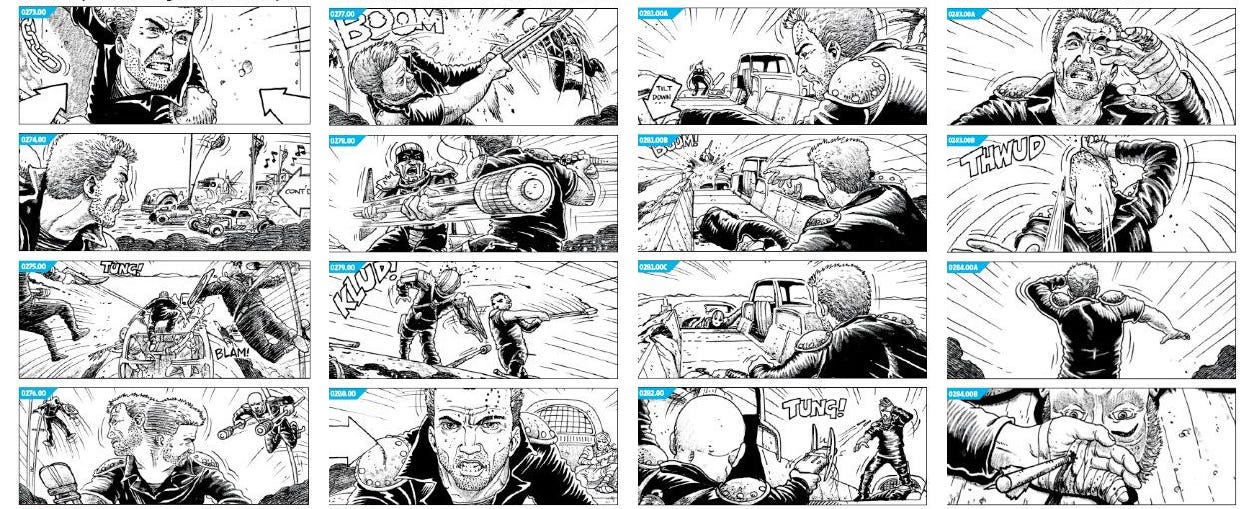

“Almost every movie is hard to make,” notes Buchanan at the beginning of Blood, Sweat & Chrome, but Fury Road went beyond those quotidian difficulties. Buchanan brings a Dantean sensibility to describing Fury Road’s particular version of production hell, cheerfully bringing his readers into each and every circle of a troubled production. The scope of Miller’s project rewards Buchanan’s oral-history format1; it took a village to make the film, and requires all of that village’s voices to even get a hold of everything that went into it. Miller began conceptualizing the movie in 1995, and didn’t get to actually start shooting it till 2012, as he alternated between making successful movies (Babe and Happy Feet) that got studio execs to buy into green-lighting a new Mad Max film and high-art box-office flops (Babe 2: Pig in the City, great film by the way) that scared off those same suits. After storyboarding out the entire movie, Miller and co. had a somewhat wary Mel Gibson on board to reprise his title role, before, well, uh, Mel Gibson’s 2000s happened, further imperiling the film. Bouncing from studio to studio, Miller and co. finally got the ball rolling with Warner Brothers in 2009, only for the initial Australian filming location to receive its second highest rainfall in 121 years, turning a barren wasteland into a lush paradise. A new location was quickly found in Namibia, Charlize Theron and Tom Hardy were locked in to the lead roles, nervous studio execs cut the shooting schedule by a month before it even started, and in 2012 the film began actually shooting. The actual shooting, I suppose, is the Purgatorio part of this Divine Production, or maybe the deepest levels of hell: shooting entailed six twelve-plus-hour days a week in the desert, freezing cold at night and blazing hot during the day, with the actors shooting Miller’s largely dialogue-free compositions off of the storyboards – a process that completely bewildered the actors, as they had no sense of what was being made – and the stunt performers and technical crew working on intensely dangerous practical stunts, all to wring seconds of footage per day. These processes mostly overlapped, as detailed by members of the cast and crew:

Robyn Glaser: It wasn’t the normal way of reading a script and seeing a breakdown. You’d see three little dots on the storyboard for tomorrow, and you’d say, “What’s this?” And they’d say, “That’s the full armada.” Those three little dots? That’s 150 stunties!

Tom Clapham: What you’re seeing on set each day might only have been Furiosa getting into the car. You’d spend a whole day on little pickups like that.

Tate Van Oudtshoorn: Out of twelve to fourteen hours a day, six days a week, they got roughly between twenty-four and thirty seconds of usable footage a day.

Edgar Wright: You would hear reports about the film being in trouble, and what you’d hear people say is “Oh yeah, on Fury Road, somedays they only shoot ten seconds.” And then you watch the film, you think, Yeah, that makes sense! Every single setup is its own little mini-movie and he’s sort of shooting live action like it’s animation.

Samantha McGrady: The hardest part of the job was trying to get into the headspace of George and P.J. and Guy, because to them, everything was second nature.

Zoë Kravitz: Everything was really abstract, even though it was very clear in George’s mind. Sometimes we would have to cross our fingers and hope that he really did know what he was talking about.

Where other filmmakers might take the easy way out and ‘fix’ everything in postproduction with CGI, Miller was guided by a different ethos: “If two vehicles were to smash into each other, why simulate it digitally when you could make it real? Then you get all those random bits you can’t predict – the way the dust reacts, and all that.” So on the one hand, you have a director obsessed with his singular, precise storyboarded vision but, on the other hand, also searching for “random bits you can’t predict” – a leaning into of some alchemical mix of control and chaos. This maniacal devotion, plus the harsh environs and breakneck schedule, made for a pressure-cooker set, with bonds of friendship and enmity just as strong among the cast and crew. Consummate pro Charlize Theron and, ahem, ‘difficult’ method actor Tom Hardy were at odds for most of the production2, leading to something of a split cast, though the various subgroups within the cast – the War Boys, mostly comprised of stuntmen having undergone an intense dramaturgical workshop to get into the head of their eminently disposable characters; the Wives, young actresses of differing experiences also put through intense workshopping, including a session with Eve Ensler; and the Vuvalini, older actresses given action roles for the first time in years, and, yes, also put through dramaturgic workshop sessions – formed intense bonds that shine through in the symphony of their performances.

After reading Buchanan’s book, some of Fury Road’s virtues seem to be the result of all the production mishaps rather than solely borne out of Miller’s auteurist instincts. The sense that every character in the movie is unique and fleshed out, even if they’re only glimpsed being crushed by the monster-truck wheel of some baroquely designed car, was borne out of those acting workshops, many of which occurred in the lull between the conception of the film and the shooting of it. The cars themselves also had plenty of time to built into the idiosyncratic machines you see in the film, each individual part labored over and thought through: why would someone have this in the Wasteland? For what reason? As the crew elucidates:

Colin Gibson: There were 88 separate vehicles that all had stories and character arcs, but there were probably 130, 135 all together: three War Rigs, two Gigahorses, doubles and triples, exploding objects, et cetera.

Shira Hockman: The set-dressing crew were amazing at making sure every single car had a character and had a backstory. Who had owned it before? What modifications had they done? Why had they decorated it in a certain way?

Dayna Grant: And the details are incredible. You had all these tiny little trinkets and things hanging everywhere in places that you would never even see in the movie.

This intense detailing would’ve been the case had the film shot in 2003, or even in 2009, but all the delays meant that everything could be pored over as thoroughly as possible.

The other main virtue of Fury Road made possible by its nightmare shoot is its narrative economy; the movie is almost entirely a chase scene, and there is not one ounce of fat on it. While much of that economy has to do with Miller’s reverence for silent films, where a maximum of information is conveyed with a minimum amount of shots, Miller also had penny-pinching studio execs breathing down his neck, forcing him to focus only on getting what was needed in Namibia (the chase sequences and elaborate fight scenes) until an exec literally flew in and pulled the plug on shooting.3 That hard stop, plus a little extra time given by a more sympathetic executive about a year later, left just enough time to get in some footage for the beginning and end of the film, but not enough time to indulge in every single thing Miller had envisioned for the film (for example, a dream sequence wherein Max births himself). The film that emerged from these delays and sudden stops, after a prodigious amount of editing by Miller’s wife, Margaret Sixel, was an absolutely temporally lean and supercharged film with, paradoxically, a years-long accrual of depth in every frame. Score a couple points for the movie being great because it “was forged in fire.”

What also emerged from Fury Road’s decades-long gestation, like Athena growing out of Zeus’s head, was Furiosa. Initially conceived as an animated film that would be part of a “transmedia” experience around Fury Road, Miller and Nico Lathouris wrote the film while working through the various characters’ backstories in Fury Road, again during the indeterminate time between conception and production. The anime version was scrapped during one of Fury Road’s hiatuses, and the runaway critical / modest box-office success of Fury Road was enough to get Warner Brothers to eventually green-light Furiosa. Though still in harsh conditions and within a tight timeframe, shooting must have felt like a breeze compared to the long and winding road of Fury Road; the film was scheduled to shoot in 2022, started on schedule, and only went a month longer than expected. Given Fury Road’s outsize cultural impact and many plaudits, Miller presumably had a blank check and the ability to tell any studio executive coming within 200 feet of his shoot to fuck off, or perhaps shoo them away with a giant flamethrower. Speaking to the press, Miller said that the studio was “much more focused, their approach to filmmaking [was] much more collaborative than it was adversarial” this time around, which I suppose is a nicer way of saying “those moronic suits finally got out of my way.”

And so Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga may be Miller’s first unfettered expression of his vision of the world of Mad Max since… 1981’s Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior, and this time his budget was roughly 80 times bigger, not to mention the added bonus of forty years of filmmaking advances: better cameras, less intrusive digital effects, and improved stunt procedure. What comes out of Miller’s expanded palette is a baggier film than Fury Road, though not in ways that are necessarily bad; it’s just that any film would be baggier than Fury Road, and this one has a structure that isn’t in perpetual overdrive. In going through Furiosa’s backstory from her childhood right up to the beginning of Fury Road, Miller finds time to idle, taking a pointillist interest in the depth that was built up but never seen in Fury Road. If that sounds at all uninteresting, well, not to worry: the rest of the movie is comprised of balletically choreographed fight and chase scenes, with Miller’s compositional eye as sharp as ever.

Furiosa begins right at the time of Furiosa’s abduction from the fabled “Green Place” of the Vuvalini; as soon as she’s reached out to pick an appropriately Edenic peach from a tree, her world is under threat, and she is captured by a marauding biker gang. (Furiosa is first played by Alyla Browne, who’s been weirdly facetuned to look like young Charlize Theron, and then Anya Taylor-Joy steps in about halfway through the film to take on the role, and she’s either doing a Charlize Theron impression, or her lines were digitally altered to sound like Theron. It’s strange, but Taylor-Joy is otherwise generally excellent in the film.) Furiosa’s mother chases after her, setting up an intense game of cat-and-mouse involving hypercharged dirtbikes and preternatural sniping ability, but Furiosa is eventually turned over to Dementus, a warlord played with particular relish by Chris Hemsworth. (These guys all look like one thousand pounds of shit have been lifted off their back when they’re not on a Marvel movie soundstage being green-screened to death.) Furiosa becomes Dementus’s prisoner and surrogate daughter, a silent shackled figure most often stuck in a cage towed behind Dementus’s three motorcycle chariot (!) along with his History Man – another Fury Road concept that couldn’t quite fit into that movie; his clothing and his body are covered in tattoos that contain the history of the world, though the utility of having said tattoos on your own face is unclear). Furiosa, through some quite literal wheeling and dealing on Dementus’s part, eventually becomes the property of Immortan Joe in the imposing Citadel, though she eventually escapes captivity and becomes part of the aforementioned engineering crew that puts together the War Rigs. She manages to stow herself away on Praetorian Jack’s (Tom Burke) Rig, showing enough mettle to become something of an apprentice Road Warrior, before trying to plot out her own ultimate escape back to the Green Place.

If you’re noticing a theme within this plot précis, it’s that Furiosa is a pretty passive character throughout the first half of the film, at the mercy of various warlords and staying silent in order to survive. If you want to read the film through the lens of production, she’s almost like one of George Miller’s own films, bandied about by various warlords (studios) with their own mercantile interests in mind; it’s only in escape from these repressive figures that she (and Miller’s films) can truly express themselves. The restraint in the first half of the film makes Furiosa’s emergence in the second half even more exciting; that emergence is twinned with the film kicking into Fury Road levels of intensity, beginning with a mid-film set-piece that reportedly took 78 straight days to film and, for lack of better words, kicks major ass. For all of Miller’s skills as a director and his abiding interest in how humanity might survive after the world ends, along with the creation and proliferation of mythic heroes, he is also a guy that knows that a key part of going to the movies is seeing really fucking cool stuff on a big screen, like guys paragliding behind motorcycles while fighting a giant War Rig. That’s cinema, baby! As Fury Road actor John Iles recounts in Buchanan’s book, after being shown a model of what was to come in Furiosa:

[the second unit director had] Lego and Mattel bikes and cars and trucks and all that sort of stuff, because we want to put bodies to bike numbers so that we can get an absolute picture of what’s going on. I said, “Mate, that’s a lot of Lego.” And he goes, “The more Lego the better, John.”

In the action sequences and in the building up of various places only mentioned in Fury Road, it’s clear Miller got to get all his Legos out, and the film is all the better for it; there might be less action altogether than in Fury Road, but it’s doled out here in more concentrated and powerful doses.

Because Furiosa was written somewhat concurrently with Fury Road and used as a reference on the set of that film, it doesn’t often feel like it’s checking off boxes in the way that other prequels do. People have already noted scenes in Fury Road that take on extra resonance after seeing Furiosa, and those connections makes sense beyond a kind of conspiratorial fan-brain because the actors did actually know Furiosa’s story as they made Fury Road. I quibbled with having to see everything that was only hinted at in Fury Road – sometimes a little mystery goes a long way, and the words “Bullet Farm” are evocative enough without seeing another postindustrial walled factory town – but then I got to see a meticulously constructed battle sequence at said Bullet Farm, and most of my criticisms withered away. Are there about 20 minutes or so of things in the film that a more ‘involved’ studio would’ve cut out, like a semi-important character named Smeg or the existence of ‘piss-boys’ who use bottles of the stuff to cool down engines? Sure, and what would’ve emerged would’ve been more meager for it, as with almost all films with the studio’s thumb on the scale. (You don’t get accidental credit for standing in the way of Fury Road.) Could Furiosa be involved more in her own movie, at the expense of a very showy Dementus? I guess, though ‘talking’ and ‘vibrant and complicated interiority’ have never been huge features of this franchise, and the title character has to survive her childhood – and emancipate herself from two separate war chiefs – before she can really participate in the action, whereas Dementus gets to play the big villain throughout, dominating the screen with a deluge of locution. The use of digital effects in Furiosa has been hotly debated essentially since its trailer debuted; though it is a little more present in Furiosa than Fury Road, I’m fairly confident, after reading Buchanan’s book, that Miller did everything he could practically, and then left some of his more baroque (and fundamentally unsafe) stunts and explosions to the effects team. (Not for nothing, Fury Road also featured a fair amount of digital intervention.) A director who spends 78 days on one sequence is probably not cutting too many corners!

If Miller’s luxuriating in the details of his own created world bother you, well, good news: They probably won’t let it happen again. Furiosa has initially struggled at the box office – which is not exactly a new phenomenon for a Miller flick, as Fury Road was outgrossed its opening weekend by Pitch Perfect 2 – and, barring an unexpectedly long run in the multiplexes in our brave new world of moviegoing (is there an imperative to see any movie in theaters when half of them will be on streaming in a month?), the film may be tagged with the dreaded word flop, just like Babe 2. Miller has stated his plan to complete a kind of loose trilogy of latter-era Mad Max films, with the last one a prospective look at Max’s time in the Wasteland in the years leading up to Fury Road.4 Having just read an excellent book about just how devoted George Miller is to his vision, I have no doubt he’ll try; the only question that remains is how ‘collaborative’ whatever producer picks up the hot, possibly piss-soaked grenade that is making these movies will be, or if a company steps to the plate at all, given Hollywood’s increasing aversion to all risk and even the slightest hint of artistry. They might make him put away all the Legos.

As we’re not yet in the post-apocalypse – just inexorably inching towards it everyday – the mythic figure we get to conjure, rather than a knight errant of the past or a road warrior of the future, is that of the uncompromising artist figure facing off against the marauding forces of commerce. This tale sustains Buchanan’s oral history and runs subtextually under the latest Mad Max film, and there’s plenty of room left for more. ‘Til next time, good luck out there, George.

Blood, Sweat & Chrome is available at your local bookstore, local library, or on Bookshop.org, where all purchases support independent bookstores across the country. Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga is in theaters now; I suggest seeing it on a really big screen with the volume way up, and bring some friends too to save the industry.

If you liked this post, please share it with a friend!

As opposed to the deluge of bad oral histories that flooded the internet from about 2014-2022, when online writers decided any event could be orally historicized, no matter how slight, coterminous with the deluge of bad talking head documentaries that have become dominant in the streaming era of television.

A marketing guy with access to the dailies remarks: “And boy fucking howdy, was it clear those two hated each other. They didn’t want to touch each other, they didn’t want to look at each other, they wouldn’t face each other if the camera wasn’t actively rolling.”

That must be the crowning moment for every little sociopath who ever dreamed of being a studio exec: the day they get to fire a bunch of people on an artistically ambitious set and say “The camera will stop on December 8, no matter what you’ve got, and that’s the end of it.”

Spoiler alert: Max is briefly seen in Furiosa, a brief interlude of a mythic figure in the background of another tale, like Aeneas fighting in the fields of Troy before running off to found Rome or Lancelot riding by in another Knight of the Round Table’s tale.

Great write-up. Can’t wait to read Buchanan’s book, and as a FURY ROAD obsessive, I’ve now seen FURIOSA twice and it has not only exceeded my impossibly high expectations, but also inching closer and closer to FURY ROAD levels of greatness which I didn’t think was possible (still need to watch it half a dozen more times to be sure though!)

If you’re interested in other “troubled movie production” books, I highly recommend "Final Cut" by Steven Bach about the HEAVEN'S GATE debacle, and also "Losing the Light" by Andrew Yule about Terry Gilliam’s awful experience making THE ADVENTURES OF BARON MUNCHAUSEN.