Let's Build a Canon: The Transit of Venus

Shirley Hazzard's astronomically sweeping novel is the first inductee into the lofty newsletter canon

Let’s Build a Canon: All canon building is stupid. And I love to do stupid things! Let’s Build a Canon will be a place to celebrate good books for no reason other than that they deserve praise. You can go ahead and call me Howard Bloom, Harold’s less-serious cousin. Today’s inductee: Shirley Hazzard’s The Transit of Venus.

There’s a specter hanging over contemporary fiction: the dollhouse problem. Rachel Cusk, while writing the Outline trilogy, claimed that she found the whole act of writing traditional fiction “fake and embarrassing” - that “making up John and Jane and having them do things together seems utterly ridiculous,” especially when one could just tell the story about themselves without the shield of fictiveness. At a reading I heard her give in 2019, John and Jane had become dolls, and the whole process of writing fiction was just like playing with your toys, putting on a little show and then expecting people to care. The Cuskian mode instead focused on autobiography and authenticity - telling your own story, and relaying the stories of others, rather than inventing anything. Rachel Cusk is good at what she does, so the Outline books work for me - because their “annihilated perspective” does something interesting to the form of the novel, and whatever invention Cusk put into those books is enough to create an effective whole. (The Outline books do have an overarching plot, damnit!)1

Still, Cusk’s admission – alongside novelistic projects like Karl Ove Knausgaard’s2 autobiographical My Struggle series – has basically paralyzed most of the literary world, as writers wonder whether it’s even possible to authentically write about anything other than themselves and their own experience. This concern dovetailed with the question of whether people could ethically and believably write ‘from’ (or at least in the character of) other perspectives – other genders, races, life experiences, et cetera – without being ‘appropriative’ or offensive.3 This increasing concern led to some silly moments - like Lionel Shriver giving a talk at a literary conference in a sombrero – but also a general chilling in the ambition of the contemporary novel. Large scale, multiple perspective, or systems-based novels are mostly out; the blinkered autofictional novel is in. That’s not to say that no good novels have come out of this general shift, but their effect is mostly muted - at the end you’ve read something fine enough, you know the author is clearly a smart person, and the book goes on your shelf, never to be thought of again.

What Rachel Cusk said is true – it is embarrassing to write fiction. Writing fiction is, as a person once tweeted but now I can’t find the link, just inventing a guy to get mad at. The doll’s house metaphor is a particularly damning comparison in its infantilization of the traditional fiction writer, making those committed to fiction seem like bumbling children inviting everyone to their tea party.4 Why invent when you could just relate? And yet it only takes a book like Shirley Hazzard’s Transit of Venus to realize that no matter how embarrassing it may seem, no matter how ‘cringeworthy’ the effort of inventing and truly understanding another kind of person may appear, it can be worth it; not only just worth it, but the path towards transcendent achievement. The leap towards understanding another is the signature risk of fiction – to face the possibility of looking foolish in order to achieve something greater. Many, many will fail and fall short of the mark, and make characters and scenarios that just don’t add up – but what’s important is to try. To further mix metaphors, the writers writing only about themselves and thinly veiled versions of their friends and family are playing it safe, just trying to get on base, while those willing to imagine the lives of others are swinging for the fences. Both ways can get you a cup of coffee in the major leagues, but one involves a little more ambition, and has the bravery to face failure.

Roberto Bolaño addressed this in his novel 2666, after a pharmacist tells a character that he prefers, for example, Melville’s “Bartleby the Scrivener” to Moby Dick:

“What a sad paradox, though Amalfitano. Now even bookish pharmacists are afraid to take on the great, imperfect, torrential works, books that blaze the path into the unknown. They choose the perfect exercises of the great masters. Or what amounts to the same thing: they want to watch the great masters spar, but they have no interest in real combat, when the great masters struggle against that something, that something that terrifies us all, that something that cows us and spurs us on, amid blood and mortal wounds and stench.”

This is typical Bolaño-an hyperbole on the subject of literature, but it does get at the heart of things: transcendent fiction is built out of that blazing into the unknown, into, yes, the ‘embarrassing.’ These are the books that make us fully connect with the dolls and the dollhouse, and make us believe in the characters despite their fictiveness. Virginia Woolf entrancingly immerses you in the world of Clarissa Dalloway, Gustave Flaubert made Emma Bovary such a real feeling character that he got letters from women asking how he had found out about their lives, and Thomas Hardy made Tess D’Urberville so real to my fiancée that she finished the book and had a list of reparative demands to the cosmos to make things right. Sure, I just named three of the greatest authors of the last 150 years, but their ability to imbue the world into their fiction is what makes them endure. They took the swing and connected.

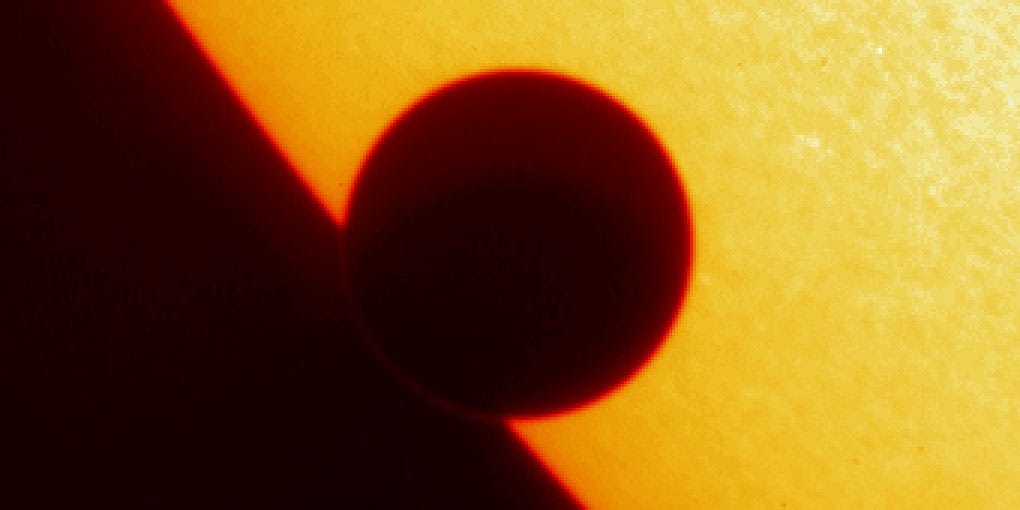

I got away from Transit of Venus there – we’re here to celebrate that book, and to watch it ascend into the heaven of this newsletter’s canon. Shirley Hazzard, in this book, gets you care deeply about each of the dolls main characters in this book over the thirty years or so it covers, mixing a Woolfian precision of character and utterly unique sentence structuring with Hardy level soap-opera plot string pulling. The sheer scale of the book, in only 300 some pages, is massive – it telescopes out into the cosmic, the truly universal, to give the story an epic cast despite its relatively quotidian milieu.

Released in 1980, The Transit of Venus principally follows Caroline (Caro) and Grace Bell, two Australian orphans who have made their way to England in the post-World War II era. Rounding out the cast are Christian Thrale, Grace’s betrothed, as well as Paul Ivory, Ted Tice, and, later on, Adam Vail, those last three being the major stars of a constellation we might call “lovers of Caroline Bell,” though that love waxes and wanes in its reciprocation. It’s stunning, reading back, to see how early each character is sharply drawn and set as a type, and how Hazzard over the course of the book commits to putting their core beliefs and types through the wringer of a life lived. Caroline and Grace are bound tightly by the deep, unknowable bonds of sisterhood, their shared “unequivocal experience … indissolubly [binding] them.” The marriage of Grace and Christian is steady5 and ho-hum in comparison to Caro’s wending road through her relationships, perhaps due to Caro’s early “crude belief… that there could be heroism, excellence … [to which] she would give her whole devotion.” Ted Tice lives the life of a schlemiel from page one, a man perpetually stuck in the rain without an umbrella, though he eventually acquires a certain kind of dignity in his resoluteness – from the get-go he is “kinetic, advanced against circumstances to a single destination.” Paul Ivory is a great aesthete, morally repellent but awfully attractive – “handsome, fair … with controlled openness” – who plays and is played by the games of higher society. Adam Vail is the great American presence introduced into the novel, and, like her countrywoman Christina Stead, Hazzard perfectly understands the American mix of naive idealism and prodigious wealth that characterizes the American 20th century. He is, at his introduction to the novel, another indomitable character, though different from Tice: “a wide, tall, motionless man, who held a black stick and stood with feet apart and his bare dark head raised,” without doubt that the world “would yield to siege.” All these characters, in ways fitting to the astronomical title, cross paths unexpectedly and gloriously, their ever-changing positions making each encounter one of one, even as their years get on and it seems as if nothing new could emerge from their relationships.

Normally I wouldn’t care too much about spoilers for a 42 year old book, and this one is great enough that knowing the various twists and turns of these character’s rich pageant lives beforehand wouldn’t ruin the book, but I do want to keep things vague here because, like I said before, Hazzard is on Thomas Hardy’s level as a pure, diabolical plot executioner, and there is a distinct pleasure in being taken along on the ride by her. Let the footnote for this sentence be ‘the spoiler zone’ for those who have already read The Transit of Venus, or who don’t care if it’s ruined.6 Hazzard herself doesn’t care about spoilers, so confident is she in her ability to tell an engrossing story: a major character’s death is revealed on page twelve of this book in a quite direct, matter of fact way. While that might sap the suspense of another novl, you get so wrapped up by the rest of this one, by the even minor beats of the story, that you either forget about it or stop caring altogether.

What captivates the reader above and beyond the highwire plotting in this novel is the style, the sentence to sentence perfection of it. Nothing is extraneous, and nothing is said in an uninteresting way. You have to again reach for greats like Woolf, Flaubert, and Henry James to find similarly crafted and consistent sentence work anywhere else in fiction. In your average novel, a reader gets one or the other - great plot or great style, and one aspect is hopefully good enough to accept the trade-off. Not here - you get peak performance in both. Close your eyes, flip to a page, and you’ll find something golden. How about this first line: “By nightfall the headlines would be reporting devastation.” How portentous! How strange the construction, the passive voice – how’d Shirley get away with that one? Who cares, let’s flip a few more pages here, to when Ted first meets Caro - “He looked up to her from his wet shoes and his wet smell and his orange blotch of cheap luggage.” And, and, and - and the blotch! That’s a sentence that will define their relationship for, oh, the rest of their lives, just tossed into the opening pages. Let’s flip a little further into the book for some average scene setting: “In a park without flower-beds or streams, on undulations of November leaves, Caro was walking alone. Branches fissured the white sky, the bark on ancient trees was corded like sinews of a strong old man.” It’s the best use of November’s bleak landscape since Melville. Here’s some wisdom from the first hundred pages that another novelist might leave for the end: "nothing creates such untruth as the wish to please or be spared something.” And how’s this for a recounting of the 1960s: “In America, a white man had been shot dead in a car, and a black man on a veranda.” Not content to stick with just America, though, Hazzard continues through the rest of the world, before getting to the cosmic – “On the moon, the crepe soul of modern man impressed the Mare Tranquillitatis” – and then the world-historical – “On the Old World, History lay like a paralysis” – before getting to the punchline on the English: “There were two new books, and a musical, on Burgess and Maclean: England was a dotard, repeating the single anecdote.”

I could become the dotard and keep copying passages from the book, until this email just became the entire text, but I’ll hold off for now, and let you get to the next pearl on your own time.

The Transit of Venus isn’t only great in comparison to the current landscape of contemporary fiction, but its successes do cast a light on the issue of whether you can write from the perspectives of others: of course you can, just make sure to do it well. It’s somewhat funny to note, against today’s fiction, that Hazzard did put her own autobiographical details into the book, particularly in the scenes of Grace and Caroline’s upbringing in Australia. All authors involve their own life in their fiction; the difference with Hazzard, and other greats, is in diffracting the self, the ‘lived experience,’ through many fictions, rather than focusing on a single ‘authenticity.’ The greats morph, embellish, and alter the truth of their lives in order to get at the real. Any canon is built to be representative to the era in which it is created; The Transit of Venus is in mine as an exemplar of the ambitious, world encompassing novel we so rarely see today. Yes, Hazzard is playing with her dolls, but by the end of the book you are crying and screaming at her to please stop the show, because she’s lit the dollhouse on fire and dear god, no, please don’t do that to the Ted Tice doll, not now – sorry, I’ve said too much.

In any case, the tide may be turning back towards – excuse the pun – the hazards of trying to imagine the world, trying to imagine the inner lives of other people, risking it all in the attempt. Rachel Cusk herself went back to a more traditional form in her latest novel, the excellent Second Place, perhaps after seeing the thousand bad Outline knockoffs she had wrought. And when Bookforum asked some of their contributors to answer a question on the future of the novel - What forms of art, activism, and literature can speak authentically today? - most of the attention went to Ottessa Moshfegh’s anti-moralist, anti-didactic answer that novelists must “reject the pressure to write for the betterment of society” and that their characters must “be free to range into the dark and wrong. How else will we understand ourselves?” That answer got after a whole different set of issues with contemporary fiction and its fixation on ‘goodness’ – more on that in another newsletter, I suppose – but nestled in that article was also an answer from the novelist Michelle Orange that took on the dollhouse problem head on:

If only my craving were simple: for a novel unconstrained by the age’s various curses, chiefly that which renders every work of art a performance of itself. I don’t read as much contemporary fiction as I’d like, in part because the curse cuts all ways. What a relief it would be to pick up a novel without the sense of participating in an attenuated dance with the author, the object of which is to keep the form we both know and love alive. The “risk” that interests me now involves retreat from that dance, an end to the mania for renovation, shallow politicking, and aesthetic primacy. Its result seeks to inhabit not a single consciousness but an intricate context, putting at its core not one striking voice but a set of bristling relationships and ideas.

The desired risk, in other words, is for one step forward by way of two steps back. If I have shared Rachel Cusk’s aversion to the “fake and embarrassing” contrivances of fiction—plot, character, world-building—my aversion to that aversion is gaining ground. In a cultural landscape more apt to fetishize its own alienation than consider it, finding a way forward for the sweeping, intimately observed social novel might be the most ambitious, surprising task a fiction writer could undertake. I’ve come around, I’m young again: show me the way from there to here, I promise I will follow.

If the writer today is to take two steps back, they might as well step back to The Transit of Venus, with the novel’s abundance of bristling relationships and ideas, its ambition, and its unrivaled achievement.

You can buy The Transit of Venus from your local bookstore, check it out from your local library, or get it online from Bookshop.org, where purchases support independent bookstores. If you liked this newsletter, please share it with a friend!

You can follow me on Twitter @evancdent, and please do consider becoming a paid subscriber to this newsletter if you’d like to support my work - you get free posts like this, commenting privileges, exclusive posts, the ability to make me review a book, and personalized book recommendations.

And you can read my MFA thesis to find out what that is!

Or, as friend of the newsletter Julie Liu calls him, Karl Nose Mouthguard.

John Updike, you have to answer for what you did in Rabbit, Redux.

The metaphor is also fun to think about historically - your early realists dragging their dolls through grimy streets and downlow milieus, your modernists making their doll go about a regular day and think way too much, your postmodernists giving their dolls funny names and making them aware that they’re dolls…

Until it isn’t - there is simply an exquisite part of the book about Christian being an absolute nonce!

Welcome to the Spoiler Zone! Seriously, I’m going to give it all away down here!!!

Hazzard goes Babe Ruth in this book and calls her shots multiple times, beginning with Ted Tice’s death on page 12 and continuing with Caro’s on page 296, the second being sneaky and clever enough to slip by undetected. This is one book that really does reward an immediate reread to pick up on the clues and foreshadowing nestled throughout the book. If Hazzard, on a sentence to sentence level, is committed to complication even when describing simple things, she does the same thing on a macro plot level, dropping ominous future plot developments in unexpected places and in seemingly unrelated interactions, misdirections on the way to book’s hellish, brutal climaxes. Paul Ivory’s crime, and Ted Tice’s witnessing of it – one of the great bits of metafictional storytelling within a story in literature, ever, and so much better for how its reveal changes the entire foundations of the characters – lives just beneath the surface for so long that Hazzard is practically taunting you with it. Anyway, I have recommended this book to many people, but now with the warning that Hazzard is an emotional terrorist, because she is at once very open about all the horrible things that are going to happen to these characters, but also talented enough to make you care deeply for them, and then rips your heart out at the end (not figuratively), and you have to sit their with the gaping hole knowing that, actually, she told you she was gonna do this all along. Ridiculous!

Nicely done. I’m firmly in the imagination camp. Though truth can be stranger than fiction! As a writer of fiction, I bow to the joy and mystery of creation. Characters just show up. It’s not a doll house, which is static. Anyway, wonderful post.