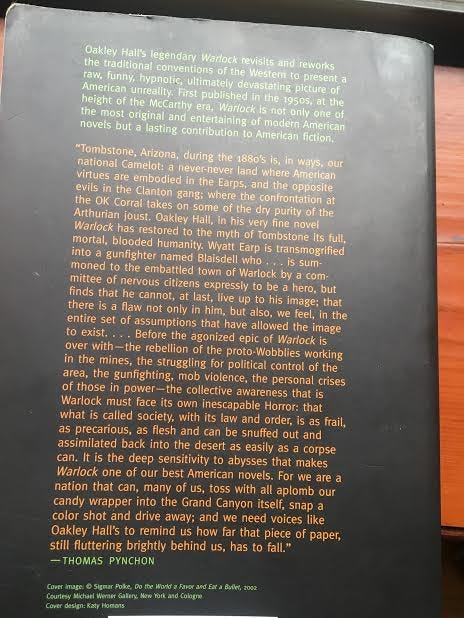

Total transparency: Isle McElroy and I text about basketball sometimes (go Raptors), and we’ve gotten a drink here and there; I wouldn’t call myself a totally impartial appreciator of their work at this point, but, to be fair, we only really became friends after I enjoyed their first novel, The Atmospherians. Our friendship is built on the foundation of Isle’s first book being good, and I’m happy to report that the second one, People Collide, is good too. I guess this is what writing a blurb is like,1 though this one will end up looking more like Thomas Pynchon’s blurb on the NYRB reissue of Oakley Hall’s Warlock:

People Collide follows Eli and Elizabeth, a young married couple living in a cramped Bulgarian apartment for the sake of Elizabeth’s prestigious fellowship in the country. (Between this and the novels of Garth Greenwell, Bulgaria is so hot right now.) They’re both writers; Elizabeth is an MFA-grad success story with agent interest and good clips, while Eli is a less successful (and less ambitious) self-taught writer in the small-press and not-read magazine/online quarterly/chapbook circuit. There’s love in their relationship, for sure, but the marriage is also one of convenience, as the fellowship would only support the husband of a fellow rather than the boyfriend – "love came secondary to the bureaucratic convenience that marriage provided.” Even then, a double bed and a balcony shared with an intrusive neighbor is all they get.

Elizabeth works as an instructor at a local school, teaching kids English and writing (or “advancing American interests”), and Eli sometimes helps at the end of the day; he’s not quite a house husband, but close, and Elizabeth’s burgeoning career is the baby he’s expected to care for. All that changes – and changes quite immediately in the novel! – when, for no reason, Eli and Elizabeth swap bodies. That’s right, it’s Freaky Friday, or 13 Going on 30, or Like Mike, or Face/Off, whatever body swap movie you prefer, but there’s no magic fortune cookie or magical pair of shoes that causes the change, and no ironic reason why the change has to happen, “No pattern. No coordinated sense of structure,” as one character says; it just happens, and Eli (with Elizabeth ‘inside’ of him) has all of a sudden gone missing.

Eli, as Elizabeth, is put the funny position of having to play the role of wife abandoned by himself. That means phone calls from Elizabeth’s parents about how bad a husband he’s been, worried attention from local friends, and having to talk to your own mother as your wife about how you’re missing (say that ten times fast). Getting used to a new body is one thing (and one that McElroy takes relish in drawing out for Eli), but Eli also has to find a way to imitate the things she would typically say or do, if not her pattern of thought, so as not to attract too much scrutiny.

A surface reading of the body swap is as a trans metaphor – McElroy is non-binary, and so autobiographical and identity-based readings come immediately to mind, even if they are to be put aside in service to the work itself – and while the particulars of Eli’s having to inhabit Elizabeth’s body do fit in this mold, the book uses the body swap conceit to more deeply delve into love and what it might mean to truly know another person at all, let alone a lover. Even after years of living together, spending nearly every day together, there are still things that Eli and Elizabeth can never know about each other without experiencing the world in their bodies. Whether that’s gaining new access to family stories via your in-laws or the simple accretions of experience that add up for someone going about their day, there are little moments that make up another’s life that can be approached but never explicated, no matter how open and honest a relationship is. (There is always something that can’t be expressed, that’s the trick of language; the trick of love is to obliterate that essential helplessness). Beyond gender performance, there are also markers of class performance that Eli must get used to within Elizabeth’s experience; she comes from a more stable and affluent upbringing than Eli, and there are innumerable rules and rituals he must quickly absorb. “This is where you find the good towels … This is what you say when you answer the phone. This how much dinner you eat.” An even deeper reading of the novel could position the swapping of bodies as a physical representation of the project and simultaneous problem of fiction: whether it’s possible to know another person, whether their lived experience can be transmitted at all by another, whether that attempt at mimesis feels real.

Eventually, in another part of Europe, Eli and Elizabeth find one another, leading to, among many things, a body-swap sex scene that singlehandedly puts paid to every contemporary prude complaint about the ‘necessity’ of sex scenes in art. Sex, like humor, is extremely hard to write well, but McElroy passes the test, ably mixing visceral details with the overwhelming strangeness of the situation (and the sensation). Eli and Elizabeth’s choice on what to do – whether to live together in each other’s bodies till they perhaps switch back, or to separate and live essentially new lives as one another – becomes a weighty question of what marriage entails, of what responsibility we hold for one another, and the limits of trust. (After all, what more could you trust one with than yourself?) “This is the ultimate act of love, Eli, inhabiting you, living as you, shitting as you. To fully inhabit your body and not run away. There’s no way to love anyone more.”

A late and unexpected perspective shift confirms McElroy’s ability to richly imagine the lives of others, as if metatextually answering the question they’ve put forward with the body swap on the problem of ficion. The shift also introduces a new relationship dynamic to be explored, between a parent and their child, who can become a new and different person once they leave the home; maybe not so literally as Eli and Elizabeth, but there is, as in marriage, an intimacy between parents and children that also has unbridgeable gaps, lacunae of knowledge that only grow with time and distance, as well as a protective impulse that has to eventually allow for independence: “I had to accept there were pains I could never prevent.”

People Collide is a refinement of the skills McElroy evinced in The Atmospherians, as well as a maturation. It confirms McElroy as one of the most exciting and inventive writers working today, someone who is comfortable playing with high concept ideas while still attuned to the minutiae that make up real, experienced life. While toning down some of the zanier satire of The Atmospherians, they maintain humor throughout the novel, something that is all too rare in contemporary fiction; there’s an echo of Lucia Berlin’s black sense of humor in the description of a poet who has the look of “a young man who died fighting unhappily for the Confederate Army. His was a face fit for daguerreotype” and a bit of Joy Williams’ ear for ‘where did that come from?’ similes in a line like “I could never shake the sense that I was, for her, like a supplementary arm grafted onto the center of her stomach.” There are few writers more attuned to the many wrinkles of gender performativity,2 whether in the masculine posturing and evasions of The Atmospherians or the subtler movements and tics that make up People Collide. And underpinning all these explorations are the fundamentals of all great novels: rock solid plotting and pacing. There’s no draggy middle section in this one, no spinning of wheels, just a well-constructed narrative that elegantly reaches an unexpected and tender ending. Cheers, Isle; next one’s on me.

You can get People Collide at your local bookstore, local library, or online at Bookshop.org, where all sales support independent bookstores (and this newsletter, if you follow the link!)

If you liked this post, please share it with a friend!

I’m available for shorter and quippier ones! I can say ‘unputdownable’ and ‘stunning’!!

This is where Judith Butler bursts through my wall like the Kool-Aid man to let me know that their definition of the word ‘performative’ does not mean this in the original formulation, but Judith, I’m sorry, the word has broken contain.

That Pynchon blurb for Warlock is fantastic.