“I have written only what I remember. If read as a history, one will object to the infinite lacunae … books based on reality are often only faint glimpses and fragments of what we have seen and heard.” - Natalia Ginzburg, Family Lexicon (translated by Jenny McPhee).

Three dirty tricks of contemporary nonfiction writing: a braided structure (sometimes called ‘the New Yorker eurostep’, or the Steven Hot Dog maneuver, where a section break introduces a jarring juxtaposition), word etymology (the most common being – and strap in for this one – the word ‘essay’ coming from the French essayer, to try), and, above all, the public excavation of a personal trauma (Something Happened to Me, or Something Happened to Me that will Clarify My Interest in this Seemingly Random Subject, In this Braided Essay). Tidily, one could trace the rise of the trauma essay with the entrenchment and ossification of New Journalism at legacy publications and the Internet Personal Essay boom of the aughts (remember Thought Catalog?) but the general idea is that Everything Can be Memoir, so make sure to get yourself in there, show off your research, and make it either relatable or wrenching, and preferably both.

Anything that runs against the no-holds-barred personal reveal ought to be celebrated as going against the current. Somewhere between the mythic purely objective piece of journalism and the navel gazing of the traditional memoir – all situation, hardly any insight – lies the truth of good nonfiction writing. We could all use more writers who know that they’re not the center of the story; an anti-memoirist, if you will. Nona Fernandez’s new book, Voyager: Constellations of Memory, translated by Natasha Wimmer, is a worthy entrant into the anti-memoir field, beginning with the trappings of traditional memoir before expanding out into space, the infinite universe, and the equally infinite spaces of the past and the future, into memory and its fallibility. It’s not about Nona Fernandez, per se; it’s about Nona Fernandez as a vessel for many stories, and what it might mean to be such a vessel: “Beyond photography and memory, where will we end up?”

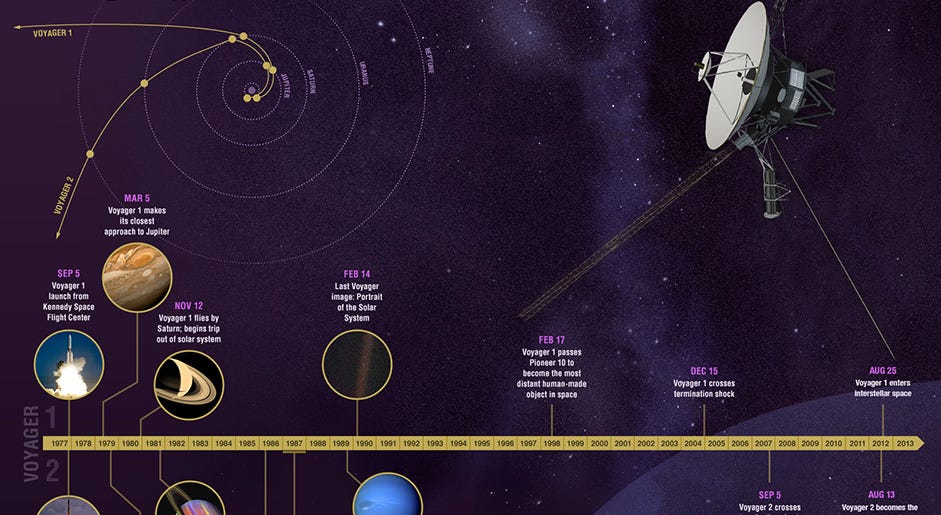

The narrative begins with Fernandez’s mother suffering from epileptic fits, which erase her memory of the minutes leading up to and during the attacks. As the doctors scan her mother’s brain, Fernandez likens the visual flashes of activity in her mother’s brain to constellations in the night sky, “an imaginary chorus of stars twinkling softly in my mother’s head… a neuronal circuit like the most complex stellar tapestry.” Following this associative thread, Fernandez likens her own mission to that of to the Voyager mission, “two space probes launched by NASA in 1977… Their task is to record. To store fragments of stellar memory.” She remembers her first time seeing constellations, and hearing her mother’s

crazy theory [she] came up with when I was little … that way up there in the night sky little people were trying to send messages with mirrors … I assumed the messages sent by those little people in the sky were to say hello and assure us they were there, despite the distance and the darkness. Hello, here we are, the little people, don’t forget us. They never stopped signaling. We couldn’t see them during the day, but they were always there … Lights from the past making a home in our present, lighting up the fearsome darkness like a beacon.

Stars – their light appearing to us from many years ago – become a direct parallel to memory, which evokes the past of many years ago in the present mind, an “act as complex as the vast fabric of the cosmos that knits itself mysteriously over our heads, enthralling and confounding us.” Memory, then, too, can be seen a signal from some far off place to not forget (from whatever metaphorical little people in the sky you’d like). Fernandez then learns of an Amnesty International effort to create a new constellation based off the names of 26 people disappeared by the Pinochet government, and is asked to become a ‘godmother’ to one of those 26 stars. A whole web opens up from there, incorporating photography, history, astronomy, astrology, genetics, her mother’s memory, a widow’s memory of her disappeared husband, her son’s life, and ultimately the national memory of Chile.

There’s a sort of zippy pace to the book, with Fernandez too interested in the next thing to stop for much raw soul bearing. (Many other writers would give in to the urge to explain at length the phrase “my son’s father,” whereas Fernandez simply drops it in and moves along, leaving all nosy readers in the dust.) If there’s such thing as a novel of ideas, then what we have here is something close to a memoir of ideas1, the development of a fascination over time, the accumulation of information that coalesces around sustained thinking. The connections in the book mean nothing beyond the fact that Fernandez has noticed them, and arranged them into their own constellation. This succession of ideas is tougher to bridge together without the easy crutch of a purely personal narrative, but Fernandez pulls it off with aplomb.

The centerpiece of the book – and the standout section – follows Fernandez as she creates a memorial to Mario Argüelles Toro, “Star HD89353,” visiting and speaking to his widow (“They took him away from me whole and I want him back whole”) and then traveling to the ceremony that will consecrate the 26 Chileans “executed by the Caravan of Death” in the night sky. The scene of the ceremony is another paradoxical space of past and present intersection, the Atacama desert, “the direst desert in the world … which means all organic decomposition processes are slowed. The abundance of salt helps mummify bodies, keeping objects intact for a long time, immune to the passage of years.” It was here where Mario and the 25 others were killed, and here where their bodies were dug up and hidden, “disappeared and disappeared again.”

Reality itself is not so precious as to present this perfectly literary setup: the desert where time slows, the idealized site of memory overlaid with the obliterative crime of murder. Fernandez doesn’t give into maudlin preciousness,2 though, undercutting her own story with the sticky particulars of life: the guide who brings the group out to the desert claims to know the area like this back of his hand before bringing them directly to a dog cemetery, a sort of sick cosmic joke on the mourners. But once they do arrive at the memorial, the scene is charged with an all the more genuine emotion, one of a communal suffering linked back across time by those who have senselessly been killed for “thinking differently,” and for those who have to live on in their stead to keep their memory alive.

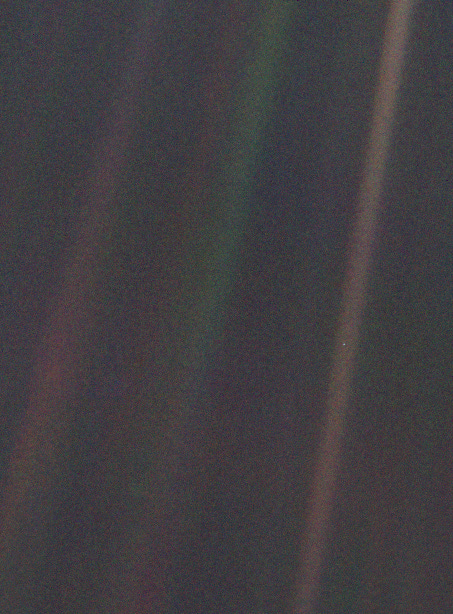

Fernandez, as a Chilean writer translated by Natasha Wimmer, is likely sick to death of comparisons to Roberto Bolaño,3 but they both write clearly and painfully about the Pinochet years, Bolaño as the exile, Fernandez as the ‘71 born child of the dictatorship. (Bolaño’s story “Sensini” – poor Gregorio! – and his novel By Night in Chile might be the ultimate documents of the Chilean exile, and Fernandez has written two books of fiction, Twilight Zone and Space Invaders, on the surreal conditions of life under the dictatorship). Where Bolaño, in both his fiction and nonfiction, is the star of the show, a writer-gladiator giving his all for the crowd, Fernandez works more obliquely, guiding the reader from behind the scenes towards revelation, weaving scattered memories into a kind of tapestry. She erases herself behind the lives of others, but you can still, with some effort, see her form behind the shroud, picking and choosing what to focus on as a reflection of her self.4 Voyager's last photo from space was pointed back towards Earth, back towards all of us, encompassing the many as it drifted further and further away from us. In nonfiction, you can put yourself in the picture or behind it; you know where my allegiances lie.

You can get Voyager: Constellations of Memory from your local bookstore, local library, or online at Bookshop.org; purchases made from that link support the newsletter and local bookstores across the country. If you liked this post, please share it with a friend!

Or, as I’ve seen elsewhere, an autobiographical essay? Words, as always, fall short.

Not only in storytelling, either! There is some word etymology in here, and explanations of myths, but for the most part the sins of precious nonfiction are avoided.

To paraphrase Bolaño himself, as he once wrote of Neruda, do we have to come back to him as we do the Cross, on bleeding knees, with punctured lungs and eyes full of tears?

This is not dissimilar to Rachel Cusk’s version of autofiction, where the narrator is oftentimes barely there, and a form I quite like when done well.

Fantastic! How big of a role does the desert play in this? Is it tangential or a central theme? Is this a ‘desert book’?

Beautiful essay, Evan.