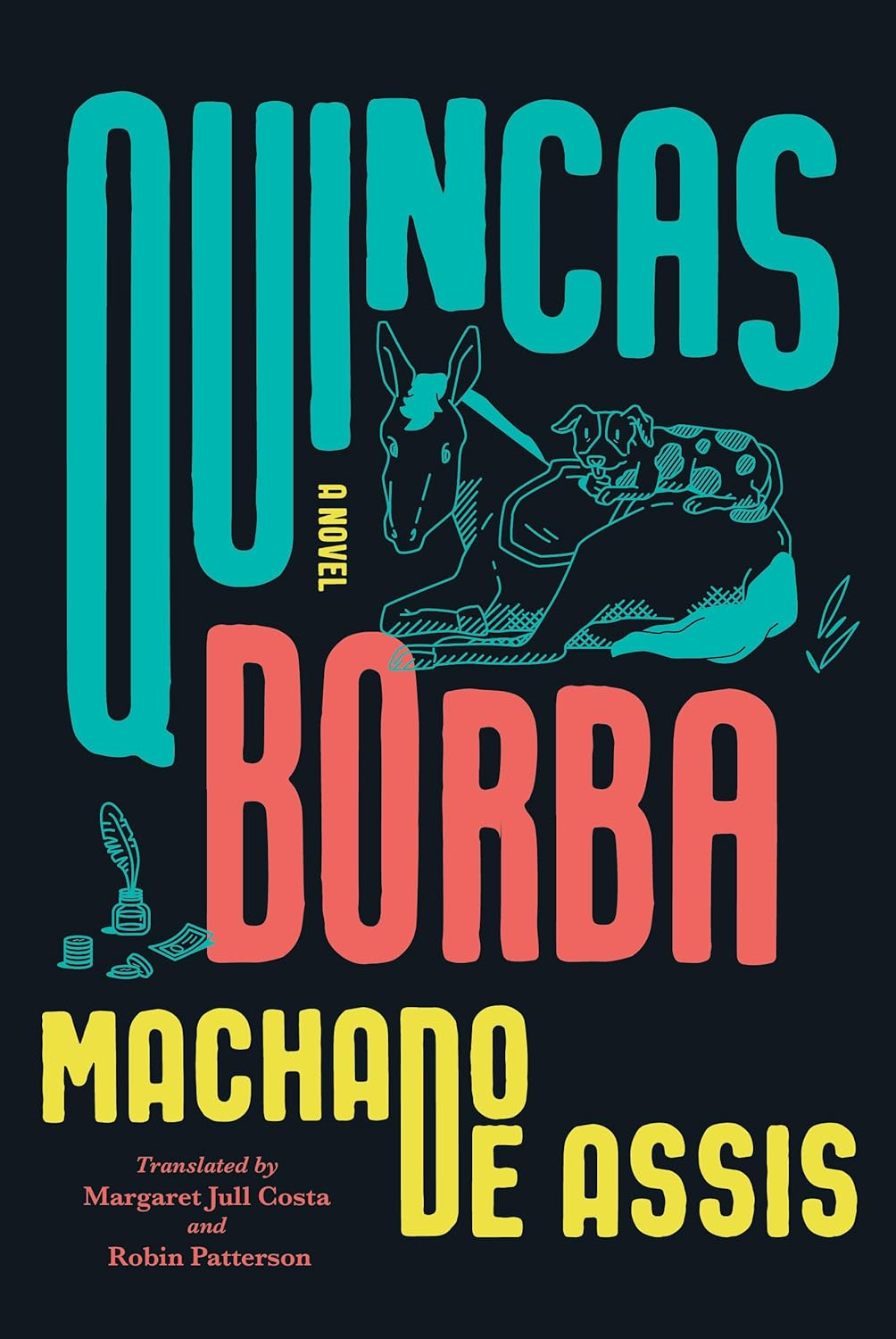

There’s not too much new under the sun; every blazing star heralding a new age has its antecedents, sometimes only revealed by the appearance of that screaming across the sky. Literary postmodernism had its heyday in the mid 20th-century, but there’s a hidden canon of authors who knowingly or unknowingly paved the way for the movement, out of step within their own times, writing books that the reading populace weren’t ready for yet, but their kids, so to speak, were gonna love it. Don Quixote and Tristam Shandy may as well be the pillars of the postmodern, loopy and self-reflexive tales that destabilized the novel just as it was coming together. (Like the Tower of Pisa, the novel was set to tilt right from the start!) Joaquin Maria Machado de Assis, a Brazilian author of the 19th century,1 has only recently gotten his shine in the Anglosphere2 as a preeminent early postmodernist; his weird little novels were only available from university presses until just a couple years ago, or otherwise saddled with oddly translated titles chosen to stop browsers in their tracks. Quincas Borba, de Assis’s 1891 novel, now out from Liveright Press in a new translation by Margaret Jull Costa and Robin Patterson, has previously been published in English under the title Philosopher or Dog?, which I suppose makes just as much sense as calling the book Quincas Borba, given that it is principally about a man named Rubião undergoing a classic rags to riches to rags story in 1860s Rio de Janeiro.

Quincas Borba is, yes, a philosopher and a dog, or, more accurately, a philosopher and his eponymous dog. (They both briefly appear in de Assis’s previous and somewhat more famous novel The Posthumous Memoirs of Bras Cubas; “if you were perhaps kind enough to read” that one, says de Assis’s narrator, he is “the very same castaway from reality who appears in my earlier book: a beggar, an unexpected heir, and the inventor of a philosophy.” ) Quincas Borba (the human) is an aged crackpot philosopher sitting on a secret fortune; Rubião, a meek schoolteacher in a small town, takes care of him in his old age, and when Quincas Borba dies, Rubião is unexpectedly bequeathed Quincas Borba’s gigantic inheritance. One condition, though: he has to keep the dog – Quincas Borba. What follows is a bit like Dostoevsky’s Idiot, as the naive yet flush Rubião enters high society and becomes an immediate target of the city’s many grifters and a mirror to society’s many ills. The narrator of this book is just a bit quirkier than Dostoevsky’s garrulous Idiot observer, much more meta, much more (post)modern, and much less obsessed with Catholicism. Plus there’s a cute dog. That dog! He easily trots into the canon of great literary dogs within the first fifty pages:

The dog bounds out. Such joy! Such enthusiasm! Such leaps and bounds around his master! He starts licking Rubião’s hand contentedly, but Rubião clips him on the nose, which hurts; he pulls back, downcast, his tail between his legs; then his master snaps his fingers, and suddenly he’s back again, joyful as ever.

‘Easy boy, easy does it!’

Quincas Borba follows him through the garden, sometimes trotting, sometimes jumping. While he savors his freedom, he never lets his master out of his sight. Here he sniffs, there he stops to scratch an ear, farther on he picks out a flea from his belly fur, then in one leap, he catches up, and is once again snapping at the heels of his master. He thinks Rubião’s thoughts are only of him, and is walking back and forth solely to have him walk, too, and make up for all the time he was kept indoors. When Rubião stops, he looks up, waiting; naturally he must be thinking of him: It’s some sort of plan for them to go out together, or something fun like that. He never considers the possibility of a sharp kick or a slap. He has a trusting nature and a very short memory when it comes to being hit. On the other hand, stroking makes a deep and lasting impression, no matter how distractedly it is done. He loves being loved. He’s happy to believe that he is.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Evan Reads to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.