Spring is in the air, baseball season’s just around the corner… wait, it’s already arrived, they played a couple games in Japan to kick things off a week ago. (Cubs lost both, of course.) Opening Day – or, I guess, what they’re calling “Domestic” Opening Day, in the spirit of “Gulf of America” – is the 27th of March this year1, which feels early, but maybe they want things to wrap up before November; last year’s World Series ended on Halloween night, just sneaking in under the wire. (The ‘Six Months out of Every Year’ of Damn Yankees is a real relic at this point.) The long promise of the season stretches out ahead, and with it an attendant hope: this could really be the year. That is, at least, if your team decided to pony up, which a shrinking number of teams decide to do these days, one of the unintended (or all too intended) consequences of the analytics revolution that took over the sport. Remember Moneyball? Michael Lewis’s book or the Brad Pitt movie? Charming little story about the shoestring-budgeted Oakland A’s finding a way to win on the margins and compete with the financial behemoths of the league? Well, at a certain point, almost every team decided to go Moneyball, even the teams in large markets, and made sure they ran their team as efficiently (read: cheaply) as possible. You either spend the bare minimum to make the playoffs and see what happens from there, or don’t spend at all and pocket the difference between your payroll and the money the league gives you for simply existing. Heck, the A’s cheaped out so much that they don’t even call Oakland home anymore; they don’t call anywhere home for the next couple years. While they wait on a stadium in Las Vegas (a city that is indifferent at best about their arrival), they’ll play, sans city name, at a minor league park in Sacramento. On the extreme other end of the spectrum, the Los Angeles Dodgers and New York Mets have decided to go against the grain, and spend ludicrous amounts of money on their players, creating a league with stratified haves and have-nots; most of the other teams have simply decided to not even try to match their spending, so there is a large, mushy middle of teams that spend just enough to be decent, hope to host a playoff game or two, but otherwise aren’t really trying.

Despite all this, I still look forward to a summer of ballgames, and hope my Chicago Cubs are one of those not-really-trying teams that manage to back into the playoffs. There’s no better sport to throw on the TV and half-pay attention to, read a book at the same time, soak in the sounds of the ballpark. A trip out to the ballpark is also a great time, couple hot dogs, a beer or two, throwing peanut shells on the ground, yakking with some pals while the game takes its own time. It might be this languorousness that has made the sport so appealing to the literay set, who’ve decided to fill in all the game’s negative space with their own words: Updike on Ted Williams, Roger Angell’s New Yorker corpus, “Casey at the Bat,” The Art of Fielding, The Great American Novel (Roth), The Natural, The Universal Baseball Association, Inc, The Index of Self-Destructive Acts, the list goes on and on. But for my money, it’s Don DeLillo who gets baseball down on the page best. His 1997 novel Underworld is decidedly not a baseball novel (unlike his novel End Zone, which is decidedly a football novel) but he begins it with “The Triumph of Death” (as it is titled as the prologue of Underworld, after a Bruegel painting) / “Pafko at the Wall” (what it’s called as a standalone story, as published in Harper’s in 1992), a panoramic recreation of The Shot Heard ‘Round the World, the 1951 pennant deciding game between the New York (baseball) Giants and the Brooklyn Dodgers. Even though it describes a dramatic ending, it’s a fitting read to begin another baseball season.

For all the sport’s supposed constancy – the national pastime is the same game as it ever was, and ever will be – the differences across eras are pretty severe. There might be as much difference between baseball now and baseball at the time DeLillo was writing “Pafko at the Wall” as there was between DeLillo writing this scene and The actual Shot Heard ‘Round The World. (There’s a damn pitch clock now!) So to read “Pafko at the Wall” now is to read a bygone era’s appreciation of an even more bygone era. Not that DeLillo is a nostalgist, but it’s clear that he’s evoking a different time, a monocultural era where millions of people’s emotions hung on a baseball game, a radio announcer’s voice beaming it to seemingly every set in the country, as opposed to the 90s’ proliferation of other interests, other sports, other mediums of dissemination. (Not to mention the relative sliver baseball gets nowadays within just the attention economy of sports.) Because it’s DeLillo, because it’s Underworld, this primal baseball scene is linked with the Cold War, the game itself occurring concurrently with a shift from a unipolar nuclear world to a multipolar one, a different kind of shot heard around the world.

This really should be the book where DeLillo writes “The future belongs to crowds,” but he already burned that excellent line a year earlier in 1991’s Mao II, so he has to get around to that kind of sentiment another way in Underworld. Third paragraph in, let’s follow the people filing into the Polo Grounds:

Longing on a large scale is what makes history. This is just a kid with a local yearning but he is part of an assembling crowd, anonymous thousands off the buses and trains, people in narrow columns tramping over the swing bridge above the river, and even if they are not a migration or a revolution, some vast shaking of the soul, they bring with them the body heat of a great city and their own small reveries and desperations, the unseen something that haunts the day – men in fedoras and sailors on shore leave, the stray tumble of their thoughts, going to a game.

Classic DeLillo - gnomic, short opening statement, unfurling description after that. The kid is Cotter Martin, jumping the turnstiles to sneak in the game – something you definitely can’t do nowadays, lest you get gang tackled by six rent-a-thugs and put on the no-fly list. All Cotter has to do is dive through and crossover one cop – “a juke step that sends him nearly to his knees and the hot dog eaters bend from the wait to watch the kid veer away in soft acceleration, showing the cop a little finger-wag bye-bye” – and then he’s up the ramp and arriving at “the great open horseshoe of the grandstand and that unfolding vision of the grass that always seems to mean he has stepped outside his life.” That - that feeling - that’s still there with any trip to the stadium, after the lines, the escalators, the one last check of the ticket, the field eventually unveils itself. Cotter Martin, like any good sneak, gets lost in the crowd, and then DeLillo takes over and casts a Brugel-esque roving eye over everyone else.

The most classically po-mo thing about the section is the presence, all together in one “choice box,” of Frank Sinatra, Jackie Gleason, Toots Shor, and J. Edgar Hoover. You know, ventriloquize the famous folks, high culture smashing into pop culture, the usual suspects, postmodernism 101. Hoover is, of course, the odd man out, but it’s all part of the job: “Fame and secrecy are the high and low ends of the same fascination, the static crackle of some libidinous thing in the world, and Edgar responds to people who have access to this energy.” Russ Hodges, the announcer behind the iconic radio call that ends the game, is also a recurring fixture in DeLillo’s panorama; in that postmodern anti-climactic mode, he’s got a scratchy throat on what will be his big day, he’s kvetching and getting through his workday just like anyone else before his call echoes into posterity. Willie Mays, out in the field, has a radio jingle stuck in his head. Amid all this, a baseball game is unhurriedly occurring as well, DeLillo pausing here and there to record, like a dutiful scorekeeper, the runs and outs.

Mostly, though, there is the crowd, a gigantic human register of emotion, a collective feeling with its own unknowable energy. However many micro-moments – a crack among friends, parents managing their children, gamblers sweating out a beat – coalescing into waves, rhythms, great swells. At once a reactive entity but also, under the right circumstances, a motivator, a creative force:

The crowd, the constant noise, the breath and hum, a basso rumble building now and then, the genderness of what they share in their experience of the game, how a man will scratch his wrist or shape a line of swearwords. And the lapping of applause that dies down quickly and is never enough. They are waiting to be carried on the sound of rally chant and rhythmic handclap, the set forms and repetitions. This is the power they keep in reserve for the right time. It is the thing that will make something happen, change the structure of the game and get them leaping to their feet, flying up together in a free thunder that shakes the place crazy.

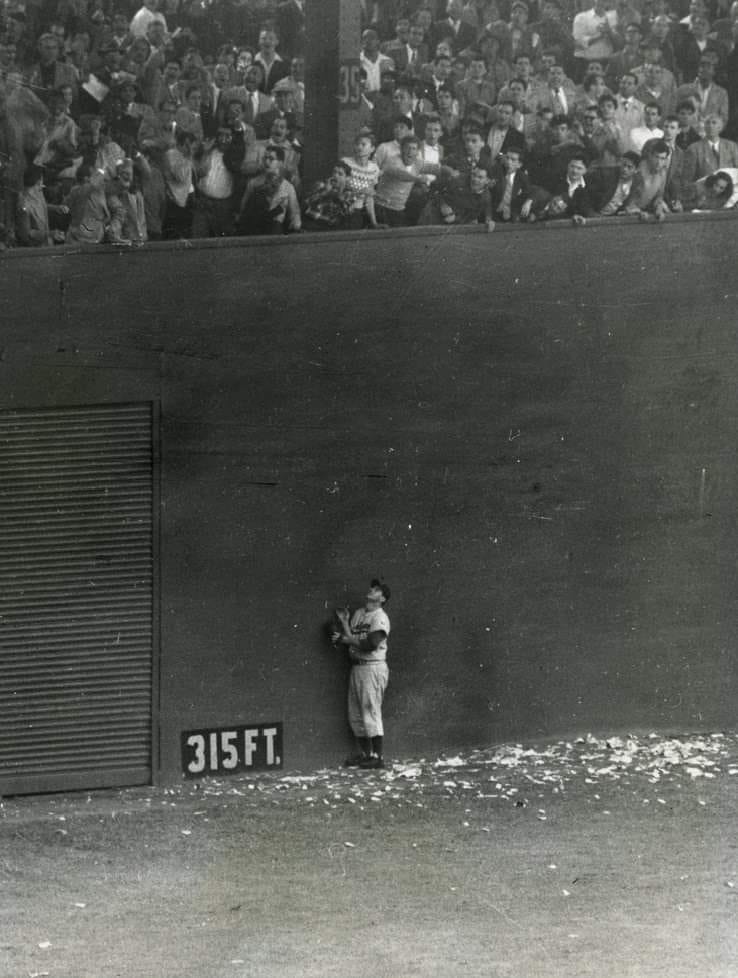

The other hysteria bubbling underneath the crowd is DeLillo’s twinned interest: nuclear anxiety. Midway through the game, a special agent hunches over and whispers in Hoover’s ear that the Russians has set off their own nuclear weapon, and thus begins another kind of rising tension: we’re waiting for the big pop of Bobby Thomson’s home run to win the game, and we’re also waiting for the big pop of the bomb. History is longing on a large scale, after all, even if that longing is for annihilation. It’s DeLillo’s trick to take the economy of scale between these two moments in history and turn them into a kind of palimpsest. The bits of paper that fall from the crowd over Pafko, the Dodgers’ poor outfielder, and over the rest of the crowd, aren’t so far off from the bits of ash falling after nuclear explosion. “Yes, Edgar fixes the date. He thinks of Pearl Harbor, just under ten years ago, he was in New York that day as well, and the news seemed to shimmer in the air, everything in photoflash, plain objects hot and charged.” It’s these moments in history that change the affective feeling of a space – the ripple or “shimmer” of news passing over the world, a collective change in consciousness.

The game builds to its inexorable conclusion – bottom of the ninth, two men on, Jackie Gleason’s puked on Frank Sinatra, ripped out pages of Life magazine blowing around the stadium, Thomson at the bat – but DeLillo has built it up so much, with so much attentive detail, that it still has a bit of a shock when Thomson’s shot rings out. As Cotter thinks after the game: “What could not happen actually happened.” Above any other connection to the sport – city pride, family roots – this is what DeLillo knows is the main draw: witnessing the impossible. Perhaps that’s why he ends the section proffering “another kind of history […] something out of here that joins them all in a rare way, that binds them to a memory with protective power.” Not longing on a large scale, but instead a kind of collective cathartic release and a codified memory:

Isn’t it possible that this midcentury moment enters the skin more lastingly than the vast shaping strategies of eminent leaders, generals steely in their sunglasses – the mapped visions that pierce our dreams? Russ wants to believe a thing like this keeps us safe in some undetermined way […] This is the people’s history and it has flesh and breath that quicken to the force of this old safe game of ours.

And so that old safe game of ours begins again this year; I can’t promise the highs of a pennant winning homer every day, but at least you can tune in along with the crowd, maybe be a part of history, maybe make your own, all that and a bag of peanuts.

You can get Underworld at your local bookstore or local library. (I haven’t seen Pafko at the Wall in many places, but it’s worth a shot.) If you must order online, ordering from Bookshop.org supports independent bookstores across the country.

If you liked this post, please share it with a friend!

That’s today, if you’re reading this the day it’s sent out!

The Underworld prologue has always been a personal favorite. I visited the Museo del Prado a few years ago specifically to see "The Triumph of Death" and it did not disappoint.