Roland Barthes' Epic Ride

Ride in this year's Tour de France on the back wheel of your favorite French semiotician

Jocks and Nerds Get Along highlights good sportswriting, good writing about sports in fiction, and any sort of intersection between sports and literature.

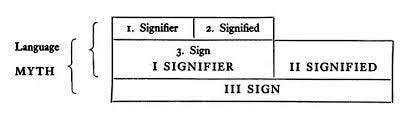

Roland Barthes: le roi of cultural studies. The murderer of the author. The man who came up with the least helpful diagram of all time:

But also, crucially for us, a sportswriter. Barthes’ book Mythologies - a collection of essays he wrote from 1954 to 1956 for the magazine Les Lettres Nouvelles - begins with an essay on wrestling (a subculture and fandom that I can’t begin to fathom, but my Twitter feed is reliably filled with otherwise normal people freaking out about wrestling every week) and also features an essay on the Tour de France, competitive cycling’s crown jewel, which runs every July.

Tour de France season is one of my favorite times of year; you can turn on the TV early in the morning and be treated to hours of beautiful French scenery while a sport even slower and less demanding of your attention than baseball occurs. You can drink your coffee, read a couple chapters of your book, and look up at the screen every once in a while to see the peloton pass some half-destroyed castle in a field of sunflowers. You only really need to pay attention to the last twenty minutes of the race, and when the race is in the mountains, you might watch a little more than usual at the midpoints. You’ll know when to look up when the announcer raises his voice even just a little bit; otherwise the Tour is just perfect background spectacle. You don’t even have to worry if you miss something - the relative inaction of the Tour means that any major incident will be replayed, discussed, and bickered over for days and possibly weeks afterwards. So if a person, just to come up with a hypothetical, holds out a sign in front of the peloton to say hi to their grandparents and causes a huge crash, you’ll see it pretty soon after. And then a couple dozen more times after that.

Barthes’ essay - “The Tour de France as Epic” - is at once totally unintelligible in its focus on the famous riders of the 1950s and weirdly timeless in its description of the race around them. As much as the Tour has changed in the 70 or so years since Barthes trained his semiotic lens on it, he still describes climbs with which today’s superior athletes continue to struggle (Mount Ventoux, for one, which the French in Barthes’ time described as so dry as to be ‘seborrheic,’ and which Barthes calls “a god of Evil to which sacrifice must be made”), the shame of doping (which “steal[s] from God the privilege of the spark”), the futility of the breakaway rider (“To lead is the most difficult action, but also the most useless; to lead is always to sacrifice oneself; it is pure heroism, destined to parade character more than to assure results”), and the pure existential sadism of the course as it is set up for the riders (“the racer is at grips not with some natural difficulty but with a veritable theme of existence”).

What’s most striking in Barthes’ essay - besides the fact that despite all technological advances in bicycling, the race remains a brutal assault on its participants - is the way that it prefigures a whole mode of sportswriting that wouldn’t become popular for another 60 years or so. Barthes was, to put it simply, the first basketblogger. For those people who weren’t paying attention to deeply online sportswriting subcultures of the late aughts, and were instead trying to get laid or something, basketblogging was a certain type of overeducated sportswriting that peaked about ten years ago and is just now reaching the end of its long tail. Barthes’ telescoped cultural critique of the Tour de France is part of basketblogging’s deep underground river of history; he helped create the distanced, critical, all-seeing eye that could tell you what was really happening amidst the spectacle of mass culture, specifically the oft-dismissed theatre of sport. Basketblogging1 was a mode of sportswriting that aspired to be more than a simple game recap, more than a cookie-cutter player profile, more than a bloviated local columnist complaining about the showboating of the star player: it married dormroom philosophy with hipster halfironic niche appreciation while also celebrating the pure fun of the game. Anyone could say LeBron James was playing well; it took a special someone to explain the hermeneutics of Bonzi Wells. Any player with any sort of idiosyncrasy was elevated and celebrated, no matter how tortured the reasoning.

I’m making it sound worse than it was - some fine pieces and writers came out of this era (including friend of the newsletter Corban Goble2); it’s just that whatever good came out of it - a sportswriting community that thought more, took itself less seriously, and was interested in cool abstract illustrations - was soon overtaken by hucksters and sellouts peddling broad pop cultural comparisons (what if the NBA… was like Game of Thrones?). The spaces where truly smart sportswriting continued to exist were slowly wiped out by the ceaseless deathprofit drive of the people who own the internet; a precious few writers continue the practice today, but most basketball writing - and sportswriting in general - has been taken over by the amateur expert, the superfan who was watched the tape and can show you four to six examples on film of whatever they’re talking about - the more niche and arcane the better. We’ve gone from discussing the dialectic tension of the James / Wade / Bosh Miami Heat to the two minute clip and attendant advanced analytic proof of how good Anthony Edwards is at making offball cuts in late game situations. It’s not quite a tragedy, but we did lose something - the enthusiast’s appreciation for the game replaced with the careerist’s all-consuming knowledge of it.

Barthes, as far as I know, didn’t seriously return to sports analysis after his magazine days; I’m sure the pure longing evident in something like A Lover’s Discourse took up most of his time, along with being a prominent academic and bringing into vogue a whole form of criticism. But if we may, we could continue Barthes’ mode of playful inquiry into the Tour de France as it rolls on now, and keep lit the eternal flame of the basketblog. The race is currently just about at its midpoint, and the presumed favorite, the two time defending champion Slovenian Tadej Pogačar, has just lost the lead and his yellow jersey. Barthes descibes in his essay the way in which riders gain their patronymic reputations, a “slow concertion of the racer’s virtues in the audible substance of his name,” and Pogačar, in the last three years of the race, had gained a single-named reputation as a climber who was unbreakable. (When you read some Barthes, it becomes really hard not to use italics.) He’s simply a climber with another gear, making other professionals regularly look foolish. No lead is safe in front of Pogačar; he’s famously said to have never “cracked”3 on a climb before this year, and he took last year’s Tour in an almost leisurely fashion.

This year’s Tour has gone differently, though: what once looked like a coronation for Pogačar now becomes a challenge that will put his championship mettle to the test. On Stage 7, Pogačar seemed to relish in letting his closest competitor, Jonas Vingegaard, get a couple bike lengths ahead of him before casually catching him in the last meters of a hellacious climb up “La Super Planche des Belles Filles.”4 His little acknowledgement to Vingegaard as they cross the line is practically evil, a little reminder that no matter how hard you try, Pogačar can do better.

On Stage 11, though, the riders of Vingegaard’s team put Pogačar through sixty kilometers of hell, repeatedly attacking him until - somehow! - they broke him. Vingegaard got his revenge, putting two and a half minutes of time between him and Pogačar in the overall race. The audaciousness of the team’s attack, though, only seems to reify Pogačar epic status - it took a whole team’s hourslong effort to bring him down. Pogačar then passed the media’s test of a noble racer - after losing his lead to Vingegaard, he came up and congratulated him after the race, displaying the sportsmanship of a truly heroic rider.

As the race continues, we’ll see if Pogačar lives up to his reputation as a Terminator-level climber who can wheel in anybody, over any timegap, or whether the legend of Vingegaard is created - he’s Danish, so look out for a celebration of his Nordic determination. Every rider, as Barthes explains, is initially classed in a nationalist way: “the racers’ names seem for the most part to come from a very old ethnic period, an age when the ‘race’ indeed was audible in a little group of exemplary phonemes.” Vingegaard has not yet gotten a diminutive or a defining characteristic besides being young, Danish, and good at climbing, but there’s time yet.

Outside of the race for the yellow jersey, the Barthesian epic characters pile up; there’s Primož Roglič, Pogačar fellow Slovenian5 and a former ski-jumper6, who had his presumed first Tour win taken away by Pogačar starmaking performance in 2020, working to help his teammate Vingegaard take the race. There are the ex-champions and contenders like Chris Froome (a four time winner still recovering from a training crash in 2019), Egan Bernal (the much hyped next big thing winner in 2019 who has been boxed out by Pogačar since) and Nairo Quintana (two time runner up, always the bridesmaid, now practically ancient in cycling years at 32) still racing along, ghosts of their former heroic selves, putting in shifts and riding not only against the terrain but against the time passing them by. There are the sprint specialists trudging through the climbs, biding their time and trying to survive so they can reach their speciality, the last kilometer, on a flat stage. There are the sturdy “domestiques” acting as the oarsmen of the ship that is the peloton, the riders who make their sacrifice for the team and team only, only nurturing a small hope that they might at one point be miraculously put in the position to win a stage. And always, always, there are the French riders, racing with a nation’s hopes on their shoulders, hoping to claim France’s first Tour win since 1985 - Romain Bardet is currently in the hunt for the yellow jersey, and the spirited Thibault Pinot is always good for an audacious yet doomed attack somewhere in the mountains.

So for the next couple weeks, if you find yourself up early, why not grab your copy of Mythologies from the English Lit class you took as an undergrad and turn on the Tour.7 The experience can be as epic or passive as you want, the grand text of the race giving as much to you as you give to it. At the very least, it’ll make your next bike ride more exciting, as the climb over Manhattan Bridge becomes the Alpe d’Huez, the rider in front of you that you just can’t catch the indomitable Pogačar, and the guy on the e-bike dangerously passing you on the downhill a Slovenian ex-ski jumper.

Though some tried to expand it to other sports, this type of writing always worked best, and had its peak, with basketball.

Subscribe to Streak Talk today!

A cycling term that perfectly describes the rider whose legs have died beneath them on an uphill.

In a linguistic move that Barthes would surely appreciate, The Planche des Belles Filles, an already famously arduous climb in the history of the Tour, has somehow found another more punishing finishing line - thus the “Super” Planche.

The English speaking media have so far not found a national characteristic to assign the Slovenians, besides the country being mountainous.

You cannot talk about Primož Roglič without saying “former ski-jumper.” It the epithet meant to display how fearless a rider he is, how daring his descents are.

It’s on TV in the US, I promise. Check your local listings!

So much to love: “basketblogger,” “underground river of history” … The Tour and its unparalleled scenery. Turning on now.